WOMAN ART WARRIOR: RENÉE COX USES HER BODY (OF WORK) TO CHANGE THE BLACK NARRATIVE

Ebony Magazine

‘Yo Mamadonna and Child,’ Renee Cox, 1994. Image: courtesy of Renee Cox.

Renée Cox isn’t afraid to put her body on the line. Over her 30-year-plus career, the artist has tackled history, race and sexuality in her work, working through the mediums of photography, collage and video. Cox has often used her own body as a canvas to challenge conventional beauty standards and power structures. The result has been mesmerizing: Cox boldly restructures Black narratives and conflicts on backdrops of wealth and comfort, disrupting prevailing narratives steeped only in impoverished backgrounds. “I like to think of my work as being reactionary to some extent,” she tells EBONY.

With exhibitions witnessed worldwide, Cox is currently showcasing Renée Cox by Renée Cox, an extensive body of her most personal work, at UTA Artist Space in Atlanta through March 23. EBONY spoke with the artist to delve deeper into her work’s themes and inspiration and explore how Black communities are encouraged to see themselves reflected in these empowered settings.

EBONY: Renée Cox by Renée Cox is truly a personal retrospect.

Renée Cox: This show is autobiographical in nature as the works start at the beginning of my career at university, from my first intervention into working with my own body all the way through The Signing. The pregnancy and motherhood part of the series is very pertinent for me as it was not welcomed information when I revealed it in 1993 to the art establishment, only to find out that women were treated as secondary citizens in the art world. And certainly, if they had children, they were not worthy of any critical attention. I had to change that single-handedly, and I believe I did. Yo Mama Donna and Child (excerpt pictured above) also touches on my Catholic upbringing.

“I was told in school that we were all created in a likeness of God. So, I felt no issue with representing myself as the Virgin Mary.”

-Renee Cox

My culture and upbringing have certainly influenced my work, from my general attitude to creating an entire body of work around Queen Nanny of the Maroons, the only female national hero in Jamaica to be honored at Heroes Stadium. I felt her life and story needed to be elaborated on and visually depicted in some way for a new generation to celebrate her veracity and strength as a Jamaican woman.

Can you talk about some of your most personal pieces?

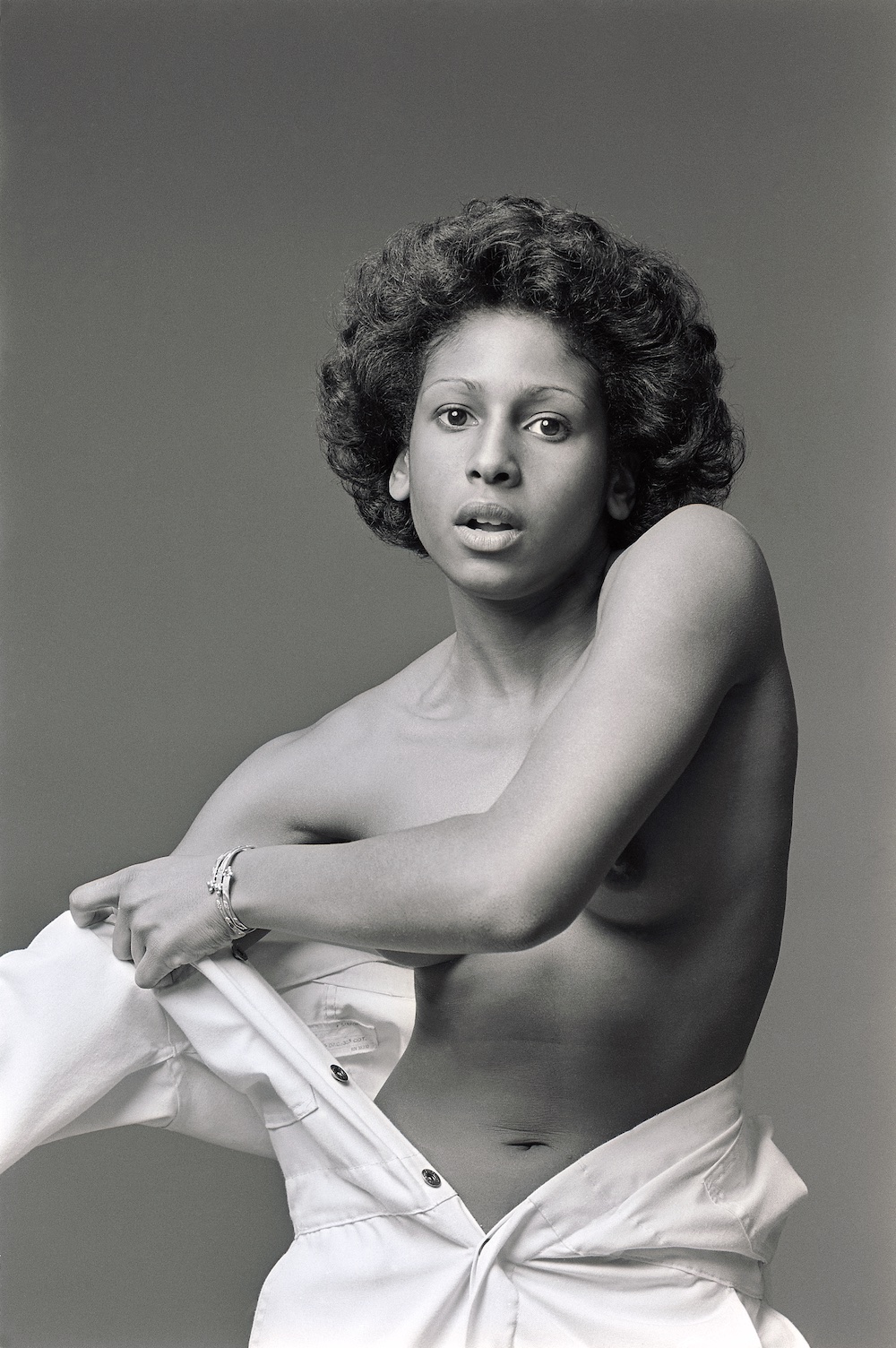

Young Yo Mama, done while I was an undergrad at Syracuse University, was the first time I disrobed in front of the camera for my own benefit. It allowed me to explore my own vulnerability but also, at the same time, claim my power and own my gaze. On the issue of motherhood, I felt it was important that women be celebrated in that capacity, unlike some of the views within the art world where if an artist is a mother, she’s deemed irrelevant and is no longer making powerful work.

Missy and The Jump Off represented a sort of midlife crisis, a depression, but also, on the bright side of that, an enlightenment and awareness of being and of self and the journey that took me from Westchester County to Bali to Peru. It was a quest to find one’s own heart and soul, which I accomplished. I’ve noticed that when Black women are going through any of these sorts of things, they’re shown in horrible settings, look horrible and are generally miserable. As poverty is not my background, I felt it was important to be able to depict Black women looking for enlightenment in settings that were conducive to what they’re accustomed to. The suffering is internal, but fortunate enough not to have to have it be external. And some of us do not live in that world. Contrary to popular opinion, we only sit on plastic slip covers with ankle bracelets around our ankles.

Why do Black women need to make art and what role do we play in making a statement about the world around us?

Black women need to make art as with anyone living person in a particular culture in a society and the time that they’re living in. I strongly believe there is a need to celebrate, interrogate, deconstruct, and unpack histories that have been created unfairly with much bias and also to liberate those who have been disrespected and undervalued in history. It’s always been my mission to uplift the Black community as a whole, especially Black women who have paid a great price for their subjugation. Having the audacity to comment on and shape discourse is about equity and autonomy, and it goes back to Jamaican upbringing of being fearless and outspoken. I have no option; I must create art. If I didn’t would mean that I would not be addressing the times that I live in, and I wouldn’t be contributing to the discourse of societal issues by providing these counter-narratives that must exist. Whenever I see something that I consider to be unjust, I feel compelled to make some sort of commentary on that; without fear. I’m also not looking for validation from the others. I give myself my own validation. For me, it’s about creating imagery that calls for new propaganda that celebrates us. It’s the attitude, it’s the fearlessness. As a Jamaican woman, I’d like to think that I operate from a platform of no fear, much in the way of Queen Nanny and much like Jamaicans do as a people.

“Black women artists play an important role in commenting on and shaping the discourse around the world we live in.”

-Renée Cox

Who are other female artists that you admire?

What’s next for Renée Cox?

I look forward to the next chapter and to total freedom of expression. I would also like to begin working on a film about Queen Nanny’s life.