Download PDF

Ernie Barnes’ iconic, musical paintings come to life at this ’70s time warp of an L.A art gallery

LA Times

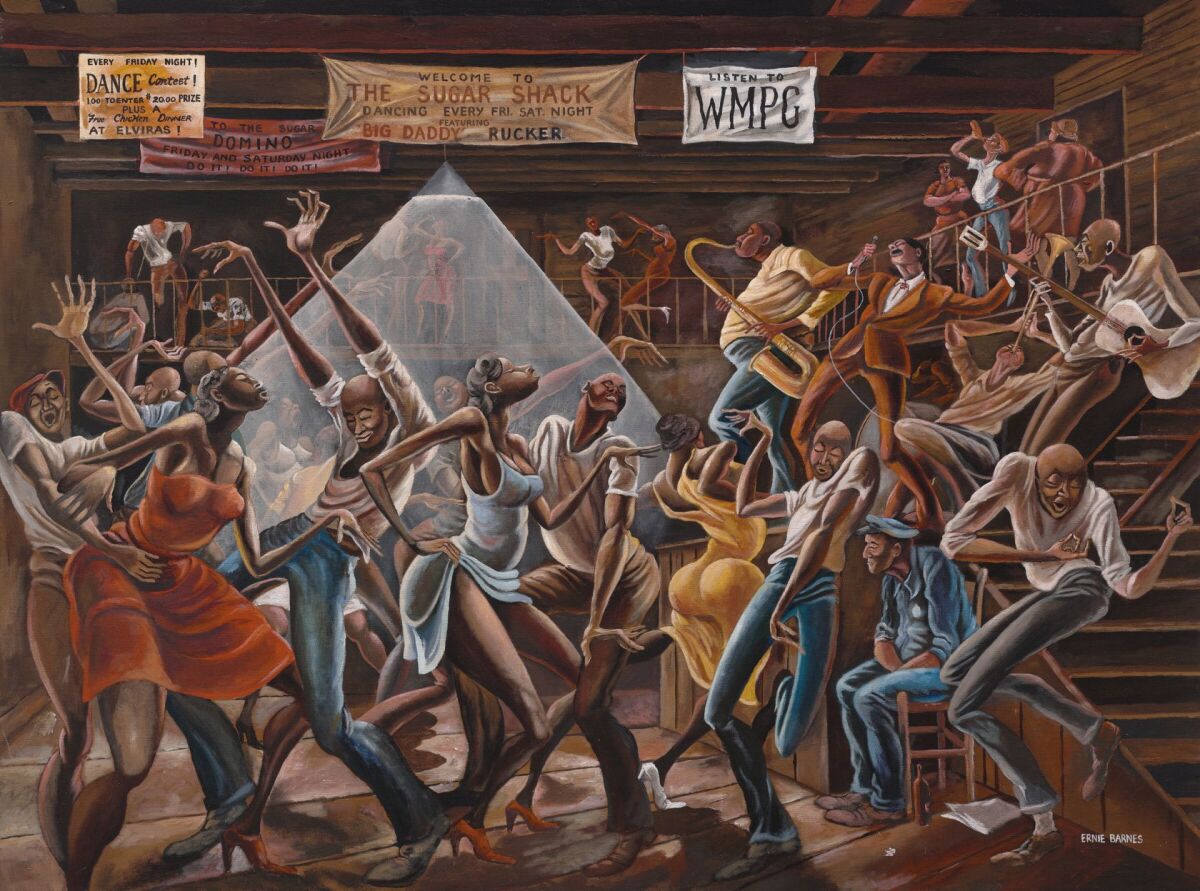

Old-school cloth banners drape across the facade of an unassuming, single-story building on a Beverly Hills side street. The central sign, meant to look hand-painted, welcomes visitors to “The Sugar Shack.” There’s a sleek vintage blue Cadillac parked on the front landing. From the street, the frosted windows appear to be crowded with the silhouettes of revelers in motion.

You want to be right in there with them, moving to what they’re grooving to. It’s the same effect that viewing an Ernie Barnes painting can have — you want to be inside his soulful depictions of crowded juke joints and dance halls, living it up while getting down.

“Ernie Barnes: Where Music and Soul Live,” offers up the next best thing. The exhibition, which opens Wednesday at UTA Artist Space Los Angeles, is a survey of the artist’s music-inspired works. (Ortuzar Projects and Andrew Kreps will co-present other of Barnes’ works at Frieze Los Angeles this week.) Once you pass through the front doors, you’re time-warped back to the 1970s, the decade associated with some of his most iconic works.

The former pro football player turned professional artist is best known for his painting “The Sugar Shack,” which was famously featured in the closing credits of the groundbreaking 1970s sitcom “Good Times.” So it’s fitting that Barnes’ portrait of the TV family the Evanses hangs in the entryway. It’s the perfect piece for priming the nostalgia pump. It’s also the only piece in which figures are still or solemn.

“Ernie’s paintings were uplifting — there’s joy, there’s nothing melancholy,” said Luz Rodriguez, director of the Ernie Barnes Estate. She partnered with UTA in November 2020 for a broader retrospective show, which was reportedly curated by the artist himself before his death in 2009. That collection roamed among such topics as the civil rights movement, sports and global warming, but “Where Music and Soul Live” is all about the beat.

The 25 works presently on display depict people in motion, overcome by the power of rhythm — whether they’re on a densely packed dance floor, in a partner’s embrace or passionately playing an instrument. UTA Artist Space director Zuzanna Ciolek describes the exhibition as “a deep dive into the importance of music in Ernie’s life and his relationship with musicians in L.A., some of them being his earliest patrons.”

Barnes counted the Staples Singers, Motown impresario Berry Gordy, record producer Lou Adler and Bill Withers among his collectors. In 2008, Withers commissioned him to create a painting inspired by his song “Grandma’s Hands.” When Barnes died the following year, the soul singer spoke at his funeral. At that same service, 5th Dimension members Marilyn McCoo and Billy Davis Jr. sang their hit “Up, Up and Away” to honor their friend.

“He loved music all his life,” Rodriguez said as she walked through the space in the run-up to the opening. She listed such inspirations as his father playing piano in the family’s Durham, N.C., home, the choirs he grew up hearing in church and the late-’80s records of Polish jazz-pop singer Basia that he’d play in his L.A. studio while painting. (“He listened to the hell out of her!”)

During his five-decade career, Barnes created artwork for seven album covers; four of those original paintings will be shown together for the first time. Visitors will get an up-close view of “Late Night DJ,” which became the cover of Curtis Mayfield’s 1980 album “Something to Believe In”; “The Maestro,” used by Houston jazz band the Crusaders for 1984’s “Ghetto Blaster”; and “In Rapture,” which graced the front of B.B. King’s 2000 release “Makin’ Love Is Good for You” with Barnes’ signature muse, the dancing woman wearing a slinky yellow dress.

And then, of course, there’s Marvin Gaye’s 1976 album “I Want You,” which placed “The Sugar Shack” front and center and prompted myriad musicians to knock on Barnes’ door seeking covers of their own. (The painting’s popularity hasn’t waned in all this time — at a Christie’s auction in May 2022, it sold for about $15.2 million.)

The relationship between Gaye and Barnes also inspired the designers at Playlab Inc., who collaborated with UTA to transform the gallery space, as they had for the 2020 show. According to Playlab’s Dillon Kogle, when the L.A.-based creative studio started conceiving design ideas in September 2022, they sought stories from Rodriguez about Barnes’ life.

“One of the stories that we honed in on was this anecdote of Marvin Gaye wanting to buy one of his paintings that he had in his car,” Kogle said, referencing an oft-told tale said to have taken place after the pair finished playing a game of pickup basketball. “The casualness of that interaction inspired the installation piece that sits outside of the UTA Space. The car is a good example of trying to pull something out of those stories that’s not necessarily pictured in the paintings … it’s bringing the soul and the life around the work to the surface.”

“We’re kind of leaving the breadcrumbs for the stories of the place and the time where these paintings were created,” his project partner Jeff Franklin added.

The team created what they’ve dubbed Club UTA. In the main gallery, a large-scale re-creation of the 1971 painting “The Disco” fills the back wall, installed above a bright red stage, where such musical guests as Compton house/hip-hop producer Channel Tres and co-founder of local artist collective Soulection, Andre Power, will perform during Wednesday’s opening reception. Stage lights bounce off a mirror ball hung from the wooden rafters of the otherwise dimly lighted room. Stacked loudspeakers are clustered in each corner and the floor is covered with vinyl that mimics the hardwood slats depicted in many of Barnes’ party scenes.

In the next room, another of the cloth banners — an allusion to common fixtures in the background of the artist’s works — bears the artist’s quote: “I work from passion. I work from human movement.” And in the final gallery, “Late Night DJ” hangs solo in an intimate backstage green room of sorts (albeit, deep purple).

“We were trying to create an engaging space that goes beyond the white-walled gallery that art is so often seen in,” Kogle said.

“We wanted to make sure that it felt like — even in its static state — movement was there,” Franklin added. “These paintings were made by Ernie to evoke a sense of fun and enjoyment around music. The challenge to us was to make a space that also had that same feeling.”