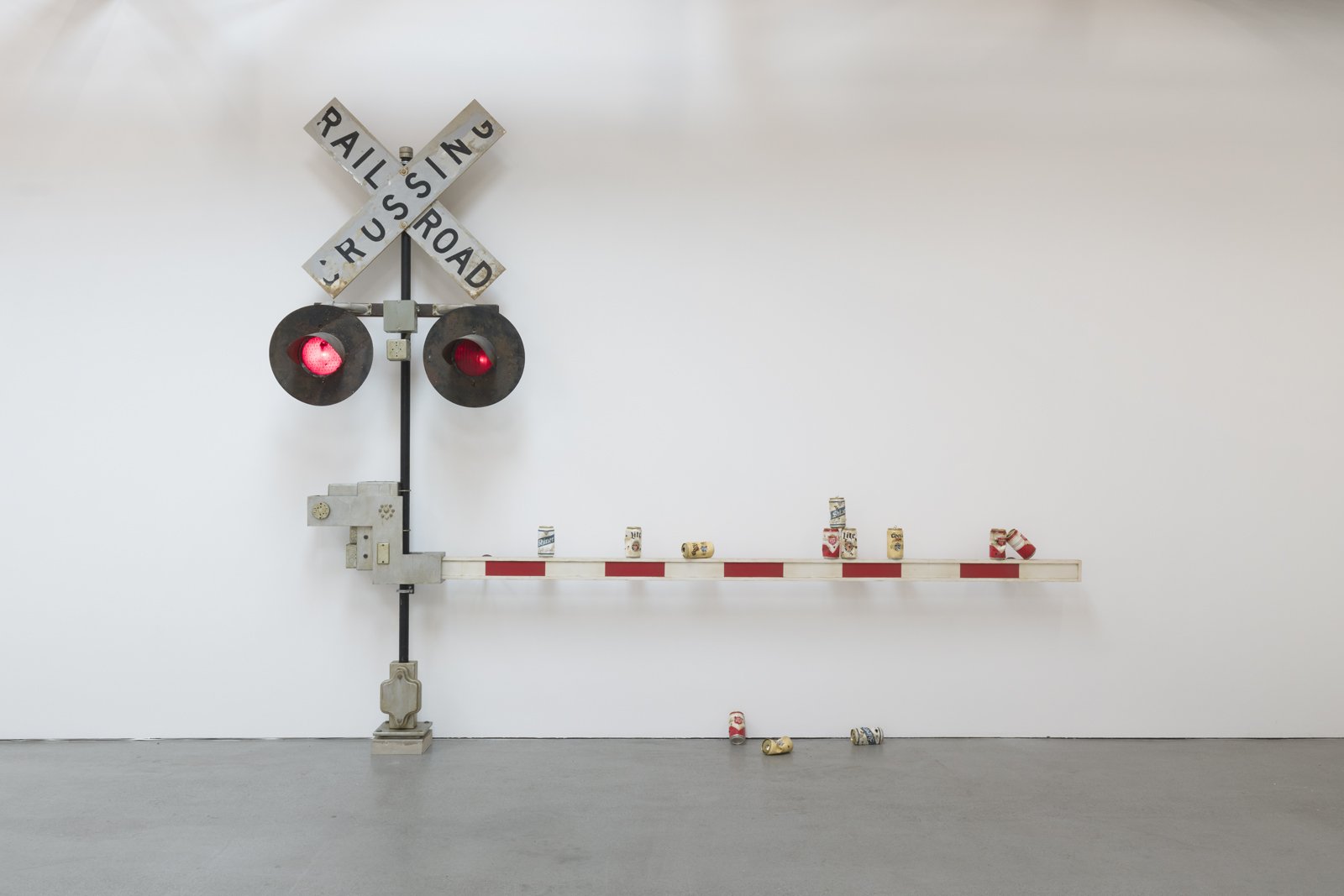

Chloe Chiasson: Bird on a Wire, Installation view, UTA Artist Space, Beverly Hills. Photographed by Jeff McLane. Courtesy of UTA Artist Space.

In this conversation, writer Ricky Amadour speaks with artists Chloe Chiasson and BANKS on their recent side-by-side exhibitions at the UTA Artist Space in Los Angeles. In Bird on a Wire, Chiasson assembles large-scale sculptural paintings that provide introspection into her upbringing in Texas and the many idiosyncracies of queer life in a small rural town. BANKS shares drawings and poems from her book, Generations of Women from the Moon (2019), which are letters to her younger self. Discussed are the themes of womanhood, the representation of the human body, and the preservation of queer history.

RICKY AMADOUR: I’m excited to speak with both of you. Chloe, Bird on A Wire, is your first exhibition on the West Coast – what is the inspiration behind the title?

CHLOE CHIASSON: I mean, particularly in my hometown [Port Neches, Texas], it doesn’t feel like it’s changed very much. The population is like 5,000 people. The air is a bit more accepting in Texas, and it’s normalized more since growing up there. But in my town, it’s not so. There aren’t queer bars, and the people who are queer still dress in very particular ways, like I did whenever I was still trying to conceal certain things. Going home after living in New York for five years is a culture shock. For the past few years, when I would go home, I felt like I had to be a different person.

RICKY AMADOUR: It also depends on what part of Texas, right? Because some places lean progressive in Texas too. There are a lot of people who think about Texas as a monolithic place.

Chloe Chiasson: Bird on a Wire, Installation view, UTA Artist Space, Beverly Hills. Photographed by Jeff McLane. Courtesy of UTA Artist Space.

CHLOE CHIASSON: You’re right; it’s not. I get that there are a lot of bad things happening in Texas, and it’s just not up to pace with the rest of the world, but it’s a much different lived experience when you’re there and growing up. It does depend on where you are, too, in the state. It’s a weird place.

RICKY AMADOUR: I have many friends in Houston, Dallas, and Austin, and it’s very different than what I initially imagined. The city centers tend to be more accepting of others.

CHLOE CHIASSON: But even in Houston, sometimes I’ll round a corner, and there’s a protesting group saying marriage equals one man and one wife. It happens in Houston, in Austin. And it’s just like, I don’t see that stuff in New York. So it’s pretty bizarre.

RICKY AMADOUR: So, BANKS, when did you and Chloe meet, and how did you decide to show together?

BANKS, Willow. Photo Credit: Jeff McLane. Courtesy of UTA Artist Space.

BANKS: Arthur Lewis came to my house and checked out all my paintings and drawings. Once we sat down and talked for a bit, he was like, you and Chloe would love each other – and he was right. When we met – we did! We didn’t meet in person, but we talked on the internet and only met the night of the gallery opening.

RICKY AMADOUR: It’s something that could only happen now in the chronological history of the world. I know you’re a musical artist. So tell me about your album SERPENTINA (2022) and how the songs are tied to the works contextually.

BANKS: When I made SERPENTINA, it was around the time I re-fell in love with drawing and painting. I did include my art on the album for the first time. It feels like one body of work – one collection of my brain.

RICKY AMADOUR: Chloe, did the album inform your work in any way? Do you listen to music when you’re making work in the studio?

CHLOE CHIASSON: I listened to BANKS’ full album after discovering we were doing the show together. BANKS knows I’ve been familiar with her music for several years. In the studio, I’ll do podcasts and stuff, but when it comes down to the wire, and I’m really trying to finish things and feel good, I always listen to country music.

RICKY AMADOUR: Who are your influences?

CHLOE CHIASSON: I’ll steer clear of going and seeing too much work because I don’t want mine to become too reminiscent of another artist’s work, which happens a lot in painting and sculpting. I try not to pull influence or inspiration from other artists.

BANKS: Hypothetically, I could go six months without making music, and then you go through something, and it finds you, and you have to express. It’s not like, “Oh, I wanna write, so let me go looking for inspiration.” It’s therapy for me. I need to write to feel better. And so yeah, it’s finding me rather than me finding it.

RICKY AMADOUR: I was thinking about taking the time to make something and how important that is. Today, I visited the “Claude Monet – Joan Mitchell, Dialogue” exhibition at the Fondation Louis Vuitton. What I found compelling about Joan Mitchell was that when she moved to France to further her painting practice, she did it because it allowed her time and space to internalize what was going on versus having to show on the gallery circuit in New York City. Here’s a question for Chloe: are your works self-portraits? Are they people in your life? Who do these people represent?

Chloe Chiasson: Bird on a Wire, Installation view, UTA Artist Space, Beverly Hills. Photographed by Jeff McLane. Courtesy of UTA Artist Space.

CHLOE CHIASSON: The faces are from photographs that I pull from the past. In the beginning, I would search for information on secret queer or lesbian bars. Some of them are known people, but most of them I’ll find in the back of a photograph from an unknown photographer. Because I use very specific faces, I make sure that they are people that feel relevant. Most of the pictures I found were from bars in London.

RICKY AMADOUR: The history of lesbian spaces lacks the same documentation as gay male spaces in a hierarchy of genders. Gay male bars are more documented – there are even maps and books of the scene in the 1800s and 1900s in places like New York City.

CHLOE CHIASSON: I think lesbian history is still happening because there was so little documentation in the past. So that’s another thing that feels important to me to contribute to – and it needs to be documented today.

RICKY AMADOUR: BANKS, I enjoyed your poem, Maybe One Day. Are you talking to your younger self? Who is the audience that you’re speaking to?

BANKS: A lot of the time, I speak to my future daughter, my younger self, and other women. It’s like we are raised to hate ourselves and feel a certain way if you’re a woman. And I think this book is the complete antithesis of all the crap and culture. It’s very maternal and nurturing, and it’s a lot of things that I wish I had heard or a poem I wish somebody had read to me when I was younger.

RICKY AMADOUR: I enjoy your poetry because it’s easy to weave yourself into it and leads you in many different directions, like The Willow Tree.

BANKS: I don’t mean to make it gender-specific. It’s not just for women. It’s similar to my music, where I write from a female perspective, but it can connect to all different types of people. If you have empathy and you’re a sensitive person, no matter who you are, you can find similarities within it.

RICKY AMADOUR: What does it mean to have femininity? And what does that mean to you?

CHLOE CHIASSON: I made femininity and masculinity coexist in my earlier work. Now I’ve gotten to the point. Where I’m from, gender roles are highly reinforced to this day. I’ll go home, and they’ll say something like, “oh, that’s a man’s work” or something, and to me, it’s just a drawing. I build everything in my work and use specific materials traditionally considered women’s craft. I like to focus on the more androgynous middle ground. When you look at the figures, you don’t necessarily know if they’re a woman or not. Some will think they’re men, and others, I believe, are a little bit more with the times and realize, “why call them a woman or a man,” you know?

RICKY AMADOUR: In your poem Dear Little Girl, you write within the poem: “to hate yourself, hate your body.” What is your outlook on how women are represented with their bodies? What does the audience take from this work, and what do you hope for them to understand?

BANKS: In pop media and culture, the representation of the female form has been objectified, dehumanized, and picked apart. Your arm should “look like this,” this should “look like this,” that should “look like that.” There are all shapes, sizes, and colors. We aren’t only our bodies – these are like the covers for our souls. I focus on what the body does for us rather than what it looks like.

RICKY AMADOUR: How do you feel about the expectations set on women to have children and the biological clock?

BANKS: I feel like it’s so funny because I think that when you’re young, just like gender norms and stereotypes of what life is supposed to be, there is conditioning to think, “I’m gonna grow up and get married and have kids.” I didn’t feel that pressure. I didn’t even know if I wanted kids until recently and who knows what will happen. I’m like, yeah, it sounds really fun to have a kid or two at this moment. I grew up in Los Angeles, so I have a much different experience than Chloe. My family is quite liberal and open-minded.

CHLOE CHIASSON: When I came out, the first heartbreak was, “oh no, my daughter’s not gonna have a wedding or get married or have kids.” It was like, “she’s a lesbian,” – so that means no kids and no man. There is an expectation for women to maintain the household, have babies, and take care of their partner.

RICKY AMADOUR: Several of my friends are freezing their eggs and have had births by surrogacy or are considering their options. It’s become so much more normalized.

CHLOE CHIASSON: It’s crazy how young people used to do it, man. It’s crazy, like at twenty.

RICKY AMADOUR: My grandma in Colombia had her first child at sixteen.

CHLOE CHIASSON: Mine did too.

BANKS: Also, if you have a baby after 35, it’s considered a geriatric pregnancy, which is hilarious.

RICKY AMADOUR: So, what did you take away from putting together this exhibition?

BANKS: I felt brave doing it because it was a new medium to express myself publicly. It was surreal. I’ve performed for thousands of people, but being in a gallery with my art hanging on the wall and watching people look at it, was more surreal to me than playing Coachella or something.

CHLOE CHIASSON: Having my family there for all of it and being my last show for the year, it felt like a good one to end on. I was lucky to do it at UTA because it was the perfect space for it.