The Four Quartets of Los Angeles

Installation Magazine

Standing behind a bouquet of crimson red roses, Enrique Martínez Celaya waits to address a host of guests. Their echoes carry from the exterior which too is lined with smaller arrangements of roses in round vases and illuminated by candlelight and spills into the gallery, creating a gentle roar. Standing shoulder to shoulder, the UTA Artist Space has exceeded its capacity but this is a moment in which one longs to be inside, an immersive environment of the artist’s own making. Everyone in attendance wants to feel the embers of the artist’s light, even if just for a moment.

Retrieving a first edition copy of T.S. Eliot’s “The Four Quartets” hidden in plain sight, nestled within a wood box, a sculpture titled, “The Entrance to the Rose Garden,” appropriately placed at the entrance of the exhibition, Celaya opens a page from the black cloth-bound book bearing a hand-painted cover of a small fire. He offers reading to illuminate the meaning of the show, the fourth concurrent solo exhibition in his home, the city of Los Angeles.

He approaches the microphone speaking in a soft cadence that is soothing to the ear and rhythmic in its inflection. His command of language gives him the confidence to summon le mot juste, comfortable in waiting for an extra breadth and never once hesitating to pause. The words will come as they always do and soon we are wrapped up in a spiral of language as delicate as the artist’s cursive hand which floats on top of the glass that houses large-scale flowers. As he is often asked to explain the narrative behind “The Rose Garden,” Celaya offers a reading that he hopes will satiate the questions not only about this exhibition but about the stories he is telling that travel across the corners of the city.

“You say I am repeating

Something I have said before. I shall say it again.

Shall I say it again? In order to arrive there,

To arrive where you are, to get from where you are

not,

You must go by a way wherein there is no ecstasy.

In order to arrive at what you do not know

You must go by a way which is the way of ignorance.

In order to possess what you do not possess

You must go by the way of dispossession.

In order to arrive at what you are not

You must go through how you are not.

And what you do not know is the only thing you know

And what you own is what you do not own

And where you are is where you are not.”

Quietly closing the page from the “East Coker,” written by Eliot in 1939, the room remains suspended in silence. We realize that the answer is inconsequential, whether we are searching for it within the UTA Artist Space or the solo exhibitions on view at The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, Fisher Museum of Art; or the Doheny Memorial Library. All that we know for certain is “what we do not know,” and this place of not knowing is precisely the search that keeps the embers glowing and the hand-painted cover is a beacon that we will call upon in our journey.

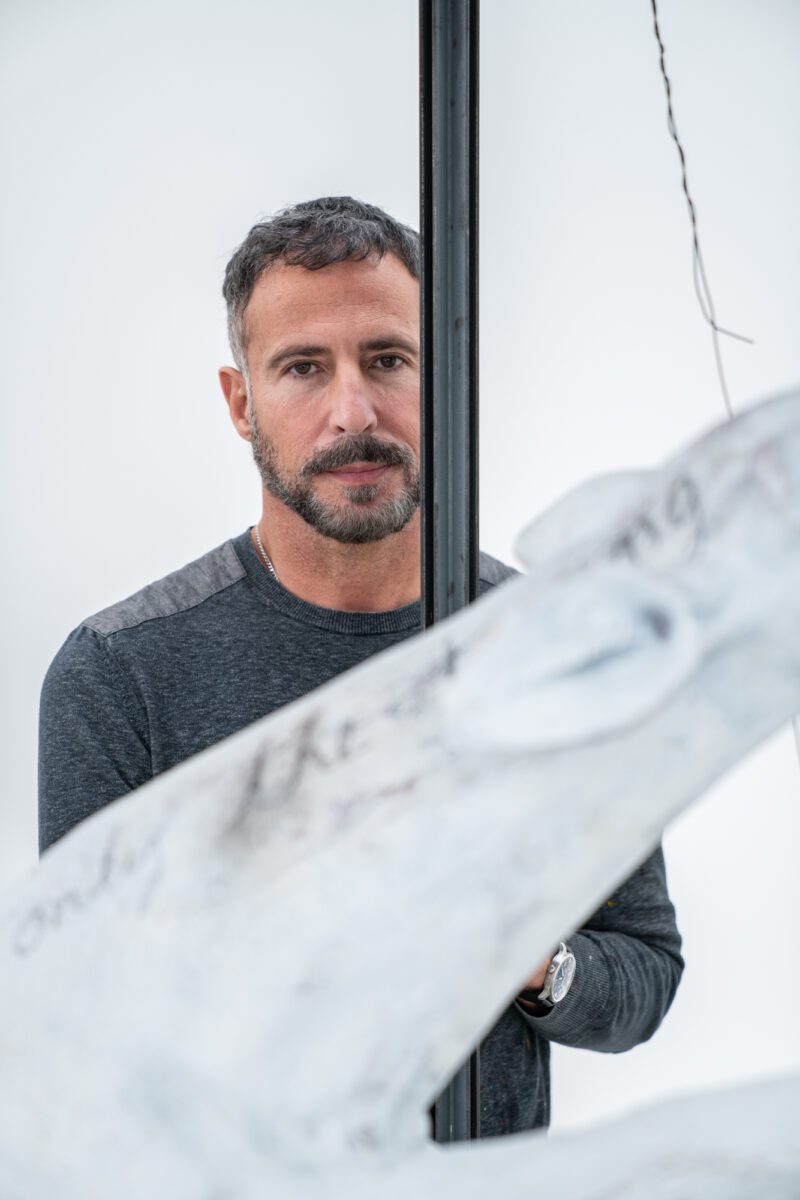

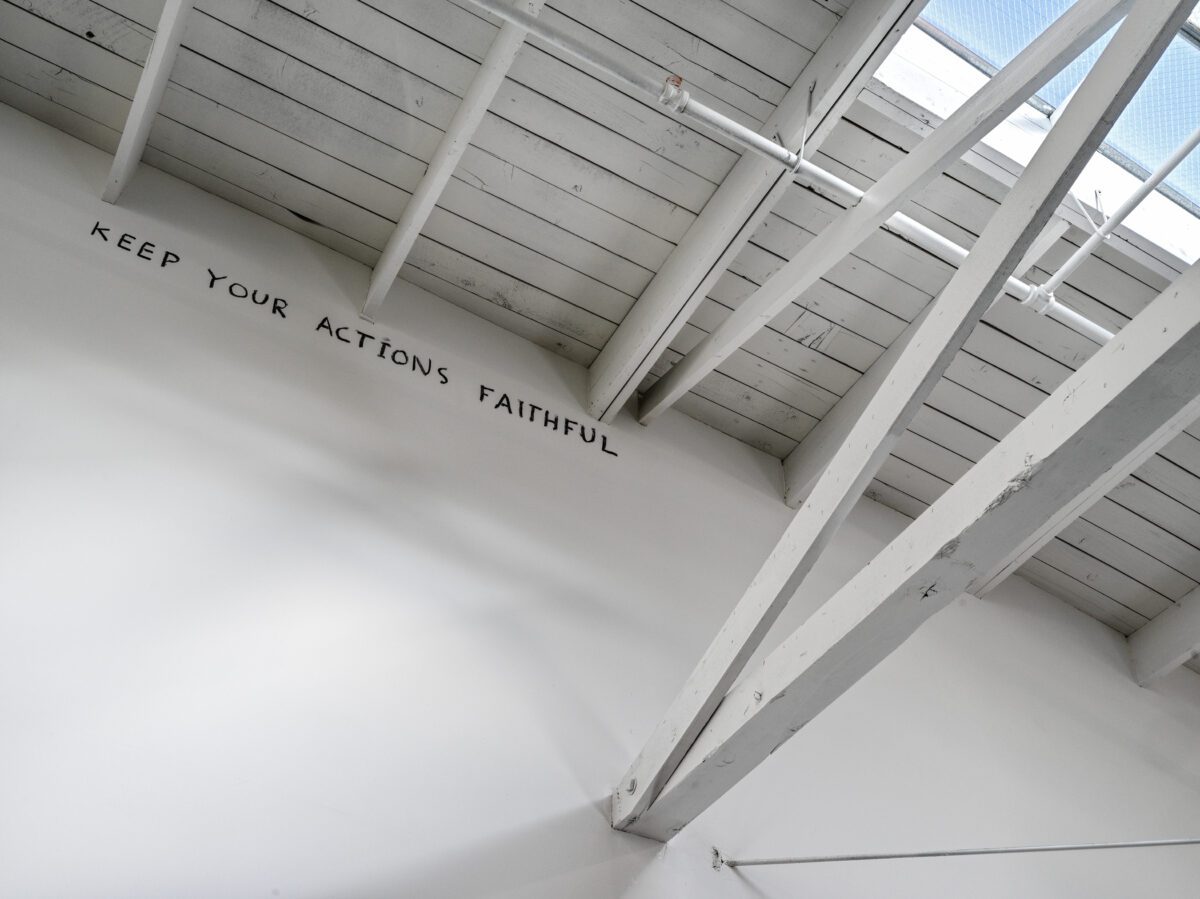

In midst of preparing for four concurrent exhibitions, Celaya has prepared a new studio. A home for his painting, writing, reading, drawing, and receiving visitors. An immaculate space where everything has a place and everything is in its right place. While its location has changed, the studio is charged with the same intention as the previous location that had become so familiar. Freshly painted white walls allow the natural light from the industrial-grade skylights to cast a warm natural glow. A work table lined with metal tubes of oil paint creates a mosaic in the afternoon sun. There is order in the overspilled paint-stained tins, home to the fading labels that contain each batch of brushes, every tool in possession of memory from past paintings and waiting to be used again. The meditation of the main studio bears the phrase, “Keep Your Actions Faithful,” which appears in a fresh coat of black paint, at the highest point of the wall directly beneath the cross beams. Normally Celaya paints during our interviews, but today all of the work is complete and the paintings will soon be transported across town to the UTA Artist Space. We take a seat on the familiar floral-patterned couch and while there is no painting that needs his attention, Celaya still wears his work uniform of fitted dark blue trousers, secured with a belt and complete with black leather boots, the laces tightened around the ankles, binding the soles of his feet to his soul.

At this moment, there are four bodies of work that create and transcend the borders of Los Angeles. Where do you feel one boundary starts and another end?

I think that in some ways, in the most strict sense of the word, we still have to include this building, which has been done at the same time. It’s concluding at the same time, which is crazy because that was not the idea, [but there] been some delays [that] made it so. If we think of installation in the broadest sense of the word, you can almost think of these five exhibitions or five events as a large installation, in the city of LA.

As the first Visual Arts Fellow of The Huntington, you were invited to intervene within the space at the end of 2021, creating a site-specific installation inside the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art titled, “There-bound.” Painting directly on the glass of the museum, the interior of the loggia, lobby, and exterior of the Galleries of American Art you engaged in a new dialogue with the surrounding gardens. Furthermore, you incorporated two of your sculptures that are already part of The Huntington’s permanent collection, “The Foundation,” and “The Gambler.” Connecting large birds and pieces of Eliot’s prose from “The Four Quartets,” is an intricate system of red and green pathways, merging and diverging, creating a system of connections. At this moment, you have four concurrent exhibitions in Los Angeles.

![]()

“There-bound” explores a narrative native to the West, the migration one undergoes to arrive at a place of promise and possibility. The birds chosen to adorn the glass of the loggia and lobby are migratory and thus an intrinsic part of their nature is to travel a border each year. The desire to arrive at a place where one feels a sense of belonging also invites a feeling of exile. What if the boundaries are blurred and the map disintegrates? This sentiment is echoed in “The Gambler,” a sculpture that is framed within the architecture of one of the large glass windows of the Galleries of American Art. A figure with crutches who struggles to put one foot in front of the other literally carries his house on his back, secured with a strap around his neck that reminds him of the weight of home with each step. While you have always worked on a large-scale, creating site-specific works and immersive environments is a new point of exploration. What has the journey been like?

I have always thought of all the exhibitions as immersive environments, even when they don’t look like that and they’re doing they’re just strict painting. But having the opportunity to start with The Huntington is exactly what you’re saying. It’s not just what to see in that gallery, around it, and in some ways, is actually the museum itself. What it is- it’s the gardens, the collection and thinking, “how can a portrait interact [within the space]? What are they commenting on partly in the collection aside from my own work?” Because there’s the traditional portraiture there. And then this idea that there’s a landscape there with the mountains, in addition to the actual gardens. And I was very interested in pushing it out and interacting with the landscape. So when I was asked to do something for “Borderlands,” as part of this fellowship and things that I wanted to really ask the question of borders- “what is the border? Not only interior and exterior, but also in the context of art exhibitions, and museums?” And all of that began to grow these ideas about what I wanted to do. And then I wanted to could relate borders and exile in some manner. And I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this question. “What are they? These fixed borders?” I wanted to acknowledge that all at the same time and think of the arbitrariness of those borders… trying to talk about that and then using the birds as a metaphor. By the time I finished doing that show, doing the work and “The Fury,” which is really very difficult painting, which I worked for many, many years, difficult emotionally and getting to the place.

At the reception for “Borderlands,” you unveiled “The Fury,” a self-portrait, which signaled yet another new point of exploration for your practice. Often your figures bear a similarity to your physicality or characteristics, however “The Fury” presented a palpable vulnerability in that it more closely resembles a self-portrait. To interact with the painting is an experiencing of seeing and being seen. We are looking directly at a man who is not hiding or averting his gaze but confronting us as he is caught in a moment of exposure. An owl, a predatory bird, and a symbol of wisdom is perched upon his head and also confronts with a piercing stare. The owl has excavated tissue from the man’s head, revealing gems of brain matter that is no longer covered by the skull but are exposed. In past studio visits, you have shared pieces that were self-portraits but would then paint over them. “The Fury” signals a moment of embracing a newfound sense of vulnerability and just as “The Four Quartets,” took six years to complete, so too did the self-portrait.

“Vulnerability” is a very good word to use there. I think humility that comes with vulnerability. To work on something for that long, is very humbling. In that, you realize your inability to do something, which is something that Eliot struggled with “The Four Quartets,” and said, “What do you have to show for it?” that kind of question. So for me, it started in a place where I felt I was not capable to bring out what needs to be brought out in that portrait and worked, and then as the arc of that movement evolved in the work, my life was changing. What would have been okay, yesterday was not okay today. So that evolution really was incredibly difficult for me in the work. And then finally, by the time I put that painting up in The Huntington, it was the most exposing. I’ve done many self-portraits in my life, but that was the most exposing self-portrait- definitely. There was no subtlety about it, there was some transgression that had happened, the way the owl will look at you and the figure looks at you, you’re very implicated as a witness to it. You are brought into some sort of difficult space, and I have not gone to that level before.

Photograph © Rainer Hosch for Installation Magazine, 2022

Photograph © Rainer Hosch for Installation Magazine, 2022

Wood box, metal bird, and first edition copy of T.S. Eliot’s “Four Quartets” with hand-painted cover and interior ink drawing by the artist.

Photograph © Rainer Hosch for Installation Magazine, 2022

The rigor of academia has always run parallel to the work that is created within the studio and presently you are the Provost Professor of Art and Humanities at USC. As reflected in the writings of Robinson Jeffers, the subject of “SEA SKY LAND: Toward a Map of Everything” at the Fisher Museum of Art, the academic pursuit cannot exist only within your mind but you must also work with your hands and physically create just as Jeffers did in moving stone by stone designing the “Tor House.” Do you feel that you have achieved a newfound sense of balance in your practice at this moment?

I feel that my work is now more confident than ever and that confidence includes these failings and comfort with the humility of those failings. So it’s not confidence because it’s like, amazing, it’s confident because this is at ease with its condition, which is very different than I felt maybe when I was younger. And that I myself can bring certain kinds of exposures in a very direct way, not sort of stowaways with a poetic sensibility, with an outright, frontally, frontal admissions of being implicated in some manner and being coming across possibly a sentiment or emotion. And I’ve been afraid that that would kidnap the work or open me up too much for ridicule. Because if you have to ridicule now I feel very confident enough in where it’s coming from, to accept it as whatever people might say about me and feel that myself at work would not be traumatized, or belittled by it, you know, people might belittle it, but what the work is doing what I’m doing is not affected by that.

Photograph © Rainer Hosch for Installation Magazine, 2022

Finally this brings us back to the origins of the studio, which is “Keep Your Actions Faithful.” You have suggested that a practice must be guided by ethics, actions, and aesthetics and that is to live, act and approach work that creates a universe of concern. It takes an incalculable number of hours for a message to run through us as natively as our own DNA, but it now feels like you are manifesting the faithful actions in an entirely new way.

Absolutely. I think in some ways, we can think of a spiral that “keep your actions faithful” is the drive towards a certain journey, rather than a destination. It’s as if each layer of that spiral as you get closer and closer to the core of things, you are constantly seeing things in ways in which you fail at that. And then just succeed, or you have to make a better effort. But there are still other parts deeper and deeper that you haven’t really been faithful to. And also when those obligations come forward and I think that’s probably an eternal process. But the deeper it gets, the less hidden that some parts are because sometimes we can people talk about integrity over time people talk about those things. And, you know, maybe you’re having clarity about some things, but other things are not maybe because we don’t know them, maybe because you don’t want to look that way. So I find that this process of aging ends up giving me some kind of question of the times in some ways.

“Time past and time future

Allow but a little consciousness.

But only in time can the moment in the rose-garden,

The moment in the draughty church at smokefall

Be remembered; involved with past and future,

Only through time is conquered.”

T.S. Eliot, “Burnt Notion,” from “The Four Quartets”

“The Four Quartets” of Enrique Martínez Celaya

“The Rose Garden”

On View Through March 12, 2022

UTA Artist Space

“There-bound”

The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

San Marino, California

On View Through November 28, 2022

“SEA SKY LAND: towards a map of everything”

Fisher Museum of Art, University of Southern California

Los Angeles, California

On View Through April 9, 2022

“Enrique Martínez Celaya and Robinson Jeffers”

Edward L. Doheny Jr. Memorial Library, University of Southern California

Los Angeles, California

On View Through April 2022

Explore the “Installation Magazine” archives with Enrique Martínez Celaya, Rainer Hosch, and A. Moret- studio visits, interviews, and photographs

Enrique Martínez Celaya, Los Angeles, CA. All Photographs of the artist and the studio © Rainer Hosch for Installation Magazine, 2022