“Power is Also Dangerous”: Ferrari Sheppard and Arthur Lewis in Conversation

Interview Magazine

Ferrari Sheppard. Courtesy of Maya Seas.

On view in Ferrari Sheppard’s new show, Positions of Power, opening today at United Talent Agency’s Artist Space in L.A., viewers find paintings of Black icons like Tupac Shakur and Jimi Hendrix alongside Sheppard’s friends and family members. None are identifiable by their faces, which Sheppard depicts without their features—a trademark of the artist’s stylized approach to figuration. Rather, he invites viewers to recognize the individuals by their body language, and the commanding presence each holds within the world of their portrait—their “regality,” as Sheppard describes it.

Sheppard’s vision of regality is derived from the Golden Age of hip-hop: its Black music and style stars, generational tastemakers, and the youth that built the culture. Twenty-four karat gold leaf abounds throughout the show, elevating Sheppard’s large-scale figures to the status of saints. A polaroid owned by Tupac forms a metaphorical altarpiece in a “shrine,” bedecked with gold floors and a Rick Owens bench contributed by the Owenscorp co-founder and designer Michèle Lamy.

Sheppard himself has moved among the demigods of contemporary music. Following his graduation from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Sheppard worked as a journalist, interviewing artists like M.I.A., Little Dragon, Earl Sweatshirt, and Erykah Badu. Shortly after, he transitioned to music production, releasing an album with Yasiin Bey (Mos Def), titled “December 99th,” in 2016. Despite his music industry success, Sheppard has always viewed himself as a visual artist, first and foremost.

Arthur Lewis, the Creative Director of UTA Fine Arts and Artist Space and a prominent collector of works by Black artists, has had his eyes on Sheppard since 2019. Interview joined Lewis and Sheppard on a Zoom call to hear the pair discuss how they met and the show they’ve created together. —ELLA HUZENIS

———

ARTHUR LEWIS: It’s nice to see you in Zoom, Mr. Sheppard. Are we not going to see your face?

FERRARI SHEPPARD: Just a second. Start video. Man, I should know this by now.

LEWIS: There you go. What’s up man?

SHEPPARD: Good. I was just having a little dance party by myself. I am doing great.

LEWIS: So I think it’d be really cool just to start with how we met—how I came to become a fan of Ferrari Sheppard—and let everyone hear that story.

SHEPPARD: Look, I was a fan of you first. I’ve been to a few shows and exhibits, and I’m a visual person. So the first thing that occurs to me, is like, “Oh man, this dude looks cool.” You had the dark frame glasses and I’m like, “This dude knows the fun.” If you get dressed, then you got style, you know?

But I’m not weird. I think it’s weird to just approach people. So it was just like, alright, whatever, it’ll happen organically. And it just so happened that Wangari [Mathenge], he was having an exhibit here, and it was an amazing exhibit. And then afterwards I came over to your house, and we didn’t get to meet officially, but we did say hello and I’ll always have some type of little book with my art or something like that. And your partner, Hau [Nguyen] was like, “What do you do?” And I showed him and he was like, “This is amazing!” And then I think he showed you, and then that kind of started our friendship.

Arthur Lewis. Courtesy of UTA.

LEWIS: It did. I think I’d seen your work that was hanging locally in a coffee and tea spot. And I remember being so captivated because you so beautifully captured this image of mother and child in this very joyful and loving state. And I’m always moved by art that tells a story, but yours had some specialness to it that I was really intrigued by. So I remember we got one painting and then acquired a second work and we hung them both in the house in a very prominent spot and had a party. And I remember telling you to buckle up. I knew how good they were. There are times when I’m wrong, but I love being right.

SHEPPARD: The coffee shop that you’re referring to is in Leimert Park, it’s a great Black-owned coffee shop called Herun Coffee. I understand that my work is really coming from, I guess you would say, a painterly fine art background or inspiration. So I thought it would be cool to just have it in the shop—and I know that the whole neighborhood was going crazy over it, because it was like, “Oh my god, there’s a museum show over here.”

Right when I met you, I was having a sort of a breakthrough in my work. For years, I started out as a figurative painter, really based in realism. And then I moved into abstraction. I stayed in abstraction for a couple of years, and this was the first time that I was merging the two together. And for subject matter, I was pulling from my experiences and the things that I saw around me, and with the mother and child painting that you had—I think it was “To Wash Away All That You Aren’t” [“To Wash Away,” 2019]—I usually never used texts in my work, but I felt like this needed that message there, to kind of bring it home, man. It’s crazy that that was like two years ago.

LEWIS: Everyone has a very emotional and visceral connection once they see [your work]. It’s just sort of an instantaneous “Wow.” So what really inspires you, my friend?

SHEPPARD: I think I would have to start at the beginning—I mean, the real beginning, with my first memory. I lived with my grandmother the first few years of my life. And at the time she had these Christmas lights, and I was under one year old, but I remember this because I would lay there every night, all night, looking at these Christmas lights and trying to figure out the size of them, the scale and reference in comparison to the room. This was as an infant. I was trying to figure out dimension and space. So that always sticks with me. And as I grew up, as the years went by, that never left. While my family members were having a great time, talking and dancing, I would study faces, and I was studying body movements. I was really interested in the natural world and also different components of how to abstract them, so that never stopped.

But I think the mode changed, because early on my whole mission in life was to capture the natural world and to make everything as real as possible. Through photography and music and different worlds of expression, I just moved into this place where now it’s almost like an antenna that goes out: instead of capturing what I see with my eyes, I’m trying to capture a feeling. I’m eating up everything. Even when we’re having a party, I’m eating up that moment because this means something more than what’s on the surface. There’s something out there. There’s a depth there that can’t be articulated through words. It has to be something that I regurgitate later, something that’s going to come out.

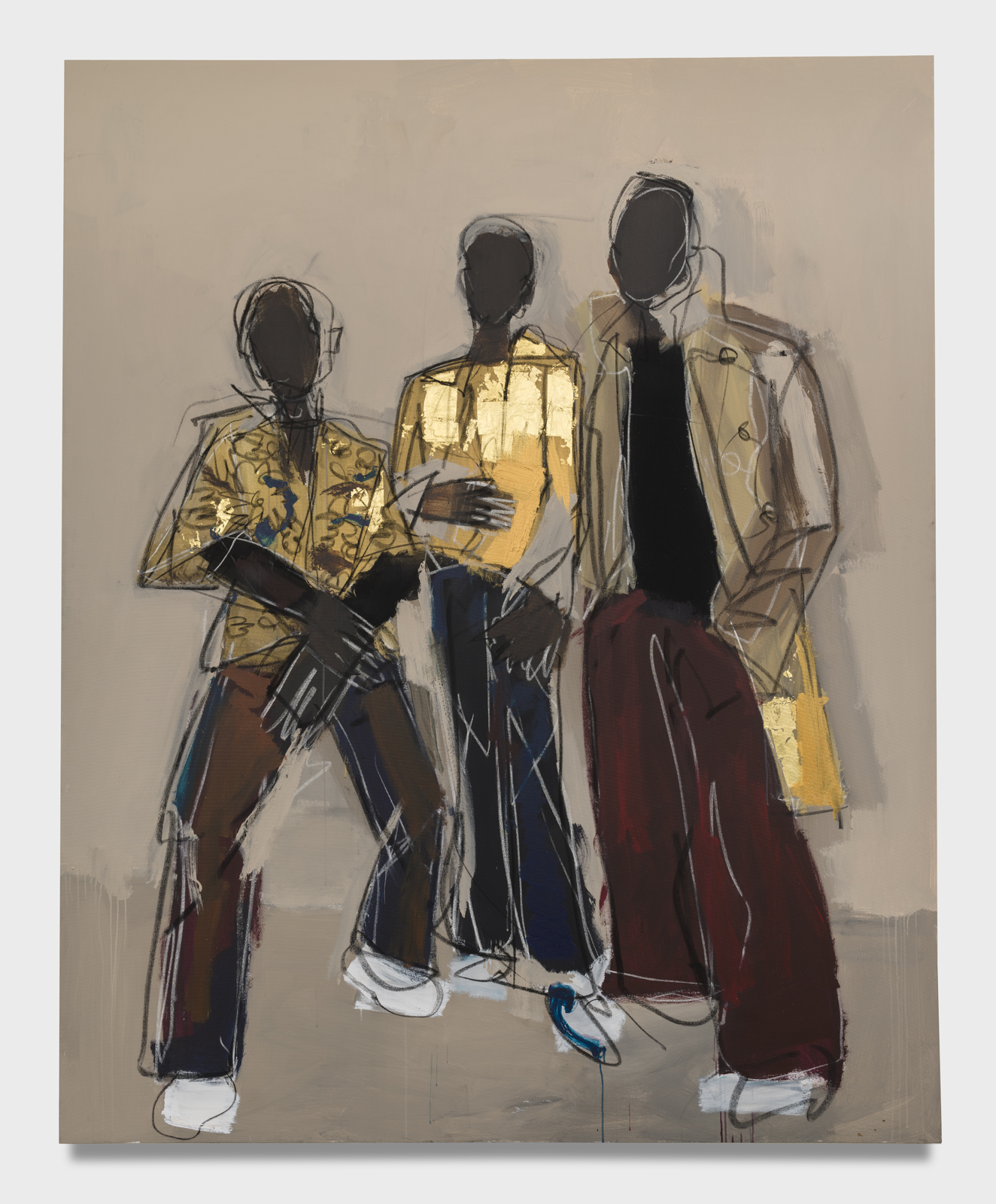

Ferrari Sheppard, “Me, Reggie, and Tavares,” 2021, Acrylic, charcoal and 24k gold on canvas, 104 x 84 inches. Photographed by Jeff McLane. Courtesy of UTA Artist Space.

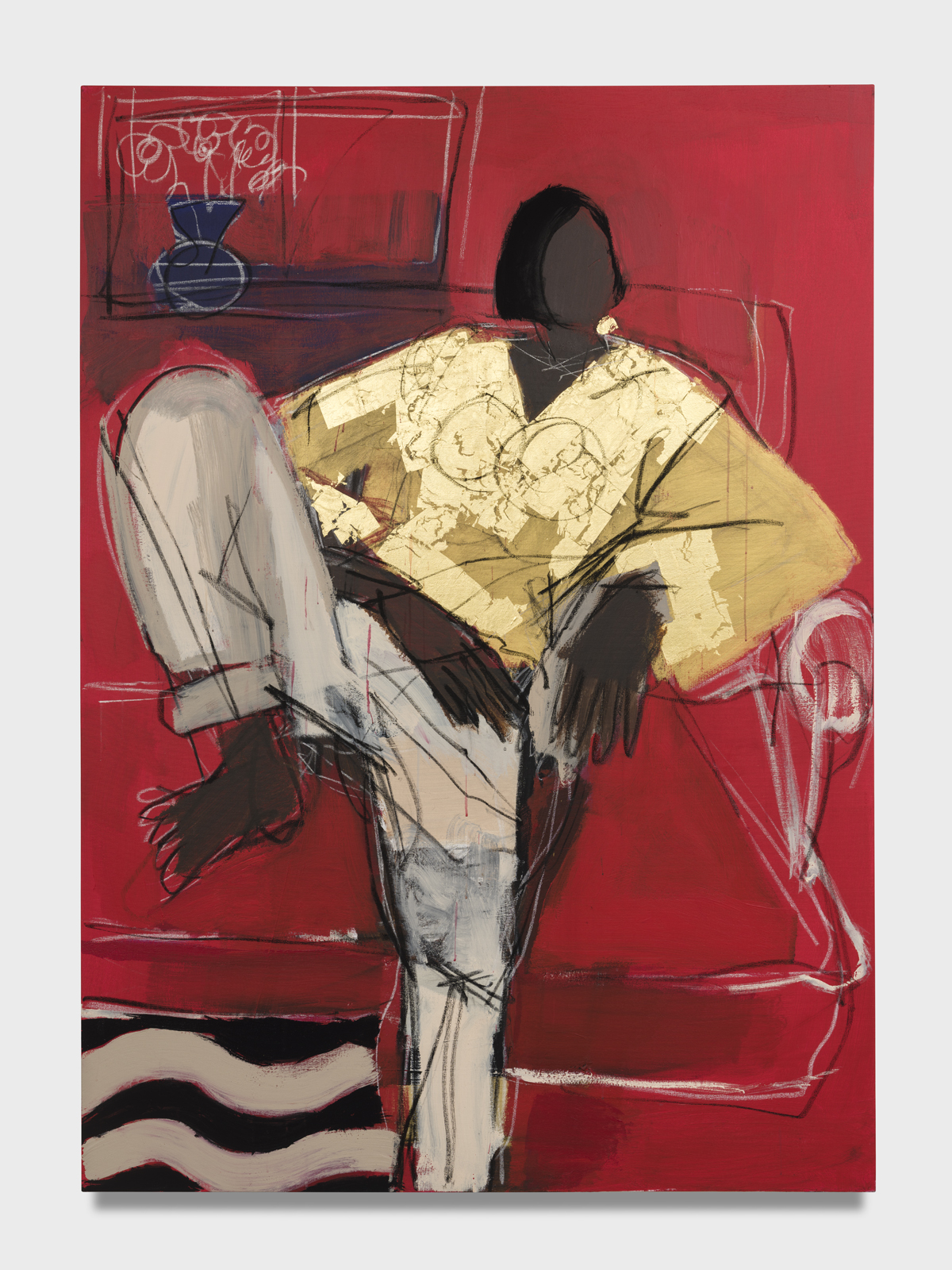

Ferrari Sheppard, “Put Some Red on It,” 2021, Acrylic, charcoal, red velvet and 24k gold on canvas, 96 x 72 inches. Photographed by Jeff McLane. Courtesy of UTA Artist Space.

LEWIS: It lives in your work. There’s so much power in how you render the subject in the work and then the environment that you place them in and the scale of the work. I can see and feel all of your influences. And I know that music played a really big role in your background. So how has that all come together for you? You had a whole other life before you became this artist.

SHEPPARD: To the outside world, they seem like disconnected periods of my life. But to me it’s very linear. They’re all one. I know these are different modes of creation, but to me they exist as one. So in terms of music, I came up in I think one of the most magical times ever, and that was the Golden Age of hip-hop—and beyond hip-hop, there was just so much going on. We were creating culture in real time and it’s almost impossible to describe what it was like to be at the epicenter of it. I thought that it would last forever. You couldn’t have told me that one day, things might take a dip. But I think it was the best time ever, and that was early in my life. It just always stuck with me. There are different periods of my life. It’s not just rap; it’s listening to my mom’s old records because she used to have, I think they were called 45s.

LEWIS: They were called 45s. Wow, you just aged me.

SHEPPARD: Yeah, they would call them 45s. I would listen to her records. And she would have the Commodores, Marvin Gaye. All of this informed my life, and had defined my life. There were times—everybody can relate to this—when you’re coming home from your relatives’ house or whatever, and it’s late and you’re listening to these songs that define your childhood. I always say the best sleep I ever had in my life is when, you’re back in the backseat and you know they’re going to wake you up to go into the house. You’re sleeping into those tunes. Honestly, I wanted to be a rap star. I came close to it, being a producer. I got to perform on The Tonight Show, and I lived that fantasy, and I loved it. But I always knew that I’m way more of a painter. I’m an artist.

LEWIS: You are an artist, and now you have this amazing career ahead of you. You and I talked about the show for quite some time and what we wanted that experience to feel like. Talk to us about the title of your show and some of the works that are in it because, personally, I think that this is collectively one of the strongest stories I’ve ever seen from an artist, putting a narrative forward and making a true statement.

SHEPPARD: Yeah. Positions of Power. For one, you would probably agree that we’re in an extremely unique time in history. Obviously we just had a pandemic, which is not unique, but it is in our lifetime. We are seeing this push by people who have been marginalized to realize their own power. And we are talking about what power actually means, the definition of power. This show kind of goes back to when I was living in South Africa and they had a little bar there—this was pre-COVID—and everybody’s dancing and stuff, and they’re playing Drake, and it dawned on me: this culture that I spoke of before has traveled all around the world, and it’s become a multi-billion dollar industry. I thought about how powerful that is, and I also thought about the creators of this culture that is being enjoyed globally. I know for a fact that they don’t necessarily know that the world is watching. I don’t think it occurs to, like, Rick Ross that you’re being watched everywhere, man, and that’s power. You have power to move people, to inspire people. And that’s what kind of started this idea, but it also goes into capitalism in general—my personal ideas about capitalism, but also my upbringing coming up during the crack epidemic. I saw it with my own eyes; my uncles and cousins, they all were enticed by this idea of, “Finally, we can have the American Dream.” They weren’t concerned with the consequences of it or how to get it, which is very American in itself. They just knew, “I feel regal inside and I want to express that and I want to have what’s on the commercials.” In some of the reference photos that I use for this show, you see that internal kind of desire being brought into the poses: “This is what we want. We want our idea of what the American Dream is.” I’m examining what power is and how it can be maintained, and how it doesn’t have to be dangerous.

A central figure in the show is an original photograph owned by Tupac Shakur. That photograph is really amazing to me because it was almost two weeks before he was released—and he came to Death Row, and we know the rest of the story—so he lived with this photograph in his prison cell. And to me, he represents, more than anything, the psyche of a young Black, talented person with so much power, but unaware of how to actually maintain it to where it’s not dangerous. Power is also dangerous. These are the conversations that I want people to have around these images. In an abstract way, there’s power in the figure. I had a color scheme: red, black, gold, and blue. It’s this bursting of energy. It’s the internal power that we all have as human beings.

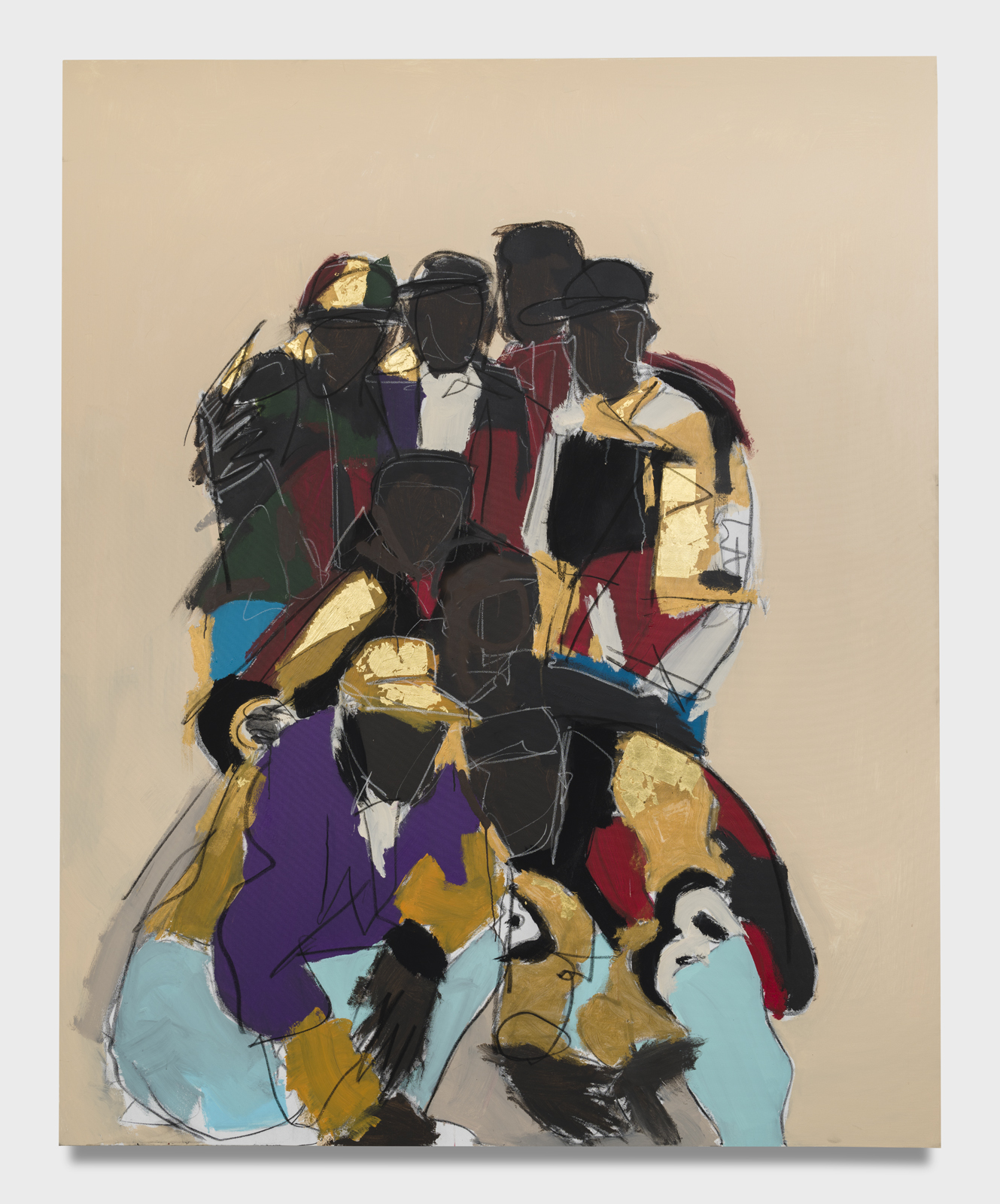

Ferrari Sheppard, “Down 4 Life,” 2021, Acrylic, charcoal and 24k gold on canvas, 104 x 84 inches. Photographed by Jeff McLane. Courtesy of UTA Artist Space.

Ferrari Sheppard, “Vita,” 2021, Acrylic, charcoal and 24k gold on canvas, 84 x 60 inches. Photographed by Jeff McLane. Courtesy of UTA Artist Space.

LEWIS: I think one of the things that the viewer is going to enjoy is not only the scale of the works, but the beauty in which you capture the figure resting in various states in this true position of almost superiority. Like, “I am here, and we are present and enjoying this.” One of the things I’m really excited about is that you’ve created a soundtrack for this show. Why was this the right moment to combine your loves together to make this show come alive?

SHEPPARD: I had my first solo show in Los Angeles during the height of the pandemic, and it turned out to be a great show. It’s beautiful. I made that work under complete distress, but you couldn’t tell if you saw the show because I was pulling from something that didn’t have anything to do with the external world. So, with UTA, I just became really excited about the space. Man, sometimes it just comes over you. There’s a spirit that comes over you. And I was like, I’m in the zone right now. And I feel privileged to even be able to tap into these things. I’m humbled because most of these days, I can’t find my house keys, so I’m just like, “How is this coming through me?”

I’m the viewer as well as the person who is bringing this to the world. So I was just so excited to tell this story in the city that has embraced me. Los Angeles has been amazing to me, and that’s basically what I would have to say about it. You know what, I’m drinking a little scotch, and I am happy right now.

LEWIS: [Laughs] That’s awesome. Well, I think so much of what has to be created is memory. I want [exhibitions] to be more than just about what you’re visibly seeing, but the feeling that you get, and wanting people to have that energy when they walk away. If you place yourself in your viewers’ position, what memory do you want them to leave this show with?

SHEPPARD: There’s one word that I could use to describe it. And it’s regality. I want them to feel regal, if only inside the confines of that show. I was watching The Sopranos the other day, and I realized, it’s a brilliant show that was very raw. It made us understand a mob boss. That’s the power of art. You may not have these experiences yourself firsthand, but great art can make you feel a little bit of what it is to be in that position. And that’s all I want for this show. I want people to feel powerful when they come and see the show.

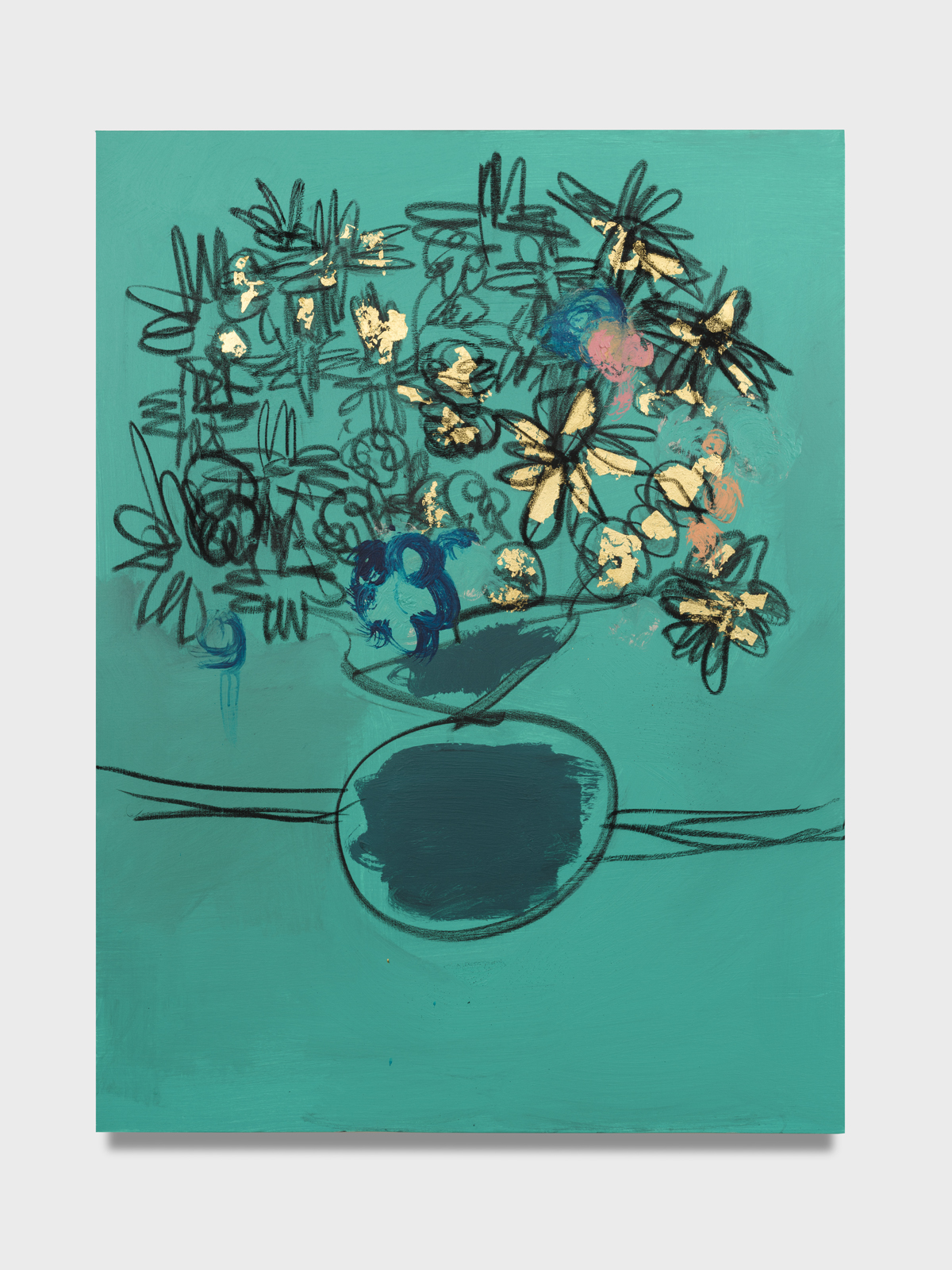

Ferrari Sheppard, “Flower Study B,” 2021, Acrylic, charcoal and 24k gold on canvas, 36 x 48 inches. Photographed by Jeff McLane. Courtesy of UTA Artist Space.

LEWIS: So, as you think back over these two years—especially this last year, which was challenging for so many people—what keeps you grateful?

SHEPPARD: First of all, I’m grateful for my health. That has never been more highlighted than this year. Health comes first, and also having some type of spiritual center, because that’s important for this life. I’m grateful for my partner. I’m grateful for you, Arthur Lewis. I understand how impossible it seems for artists, who have a dream of being famous or rich. It seems so far away, and I know how many things must align in order for that to come to fruition. And I’m just grateful that I’m in the conversation. I don’t have to be the best artist. I’m just in the conversation. I’m grateful for that.