DISEMBODIMENT: PAINTINGS FROM THE BLACK VANGUARD

LA Weekly

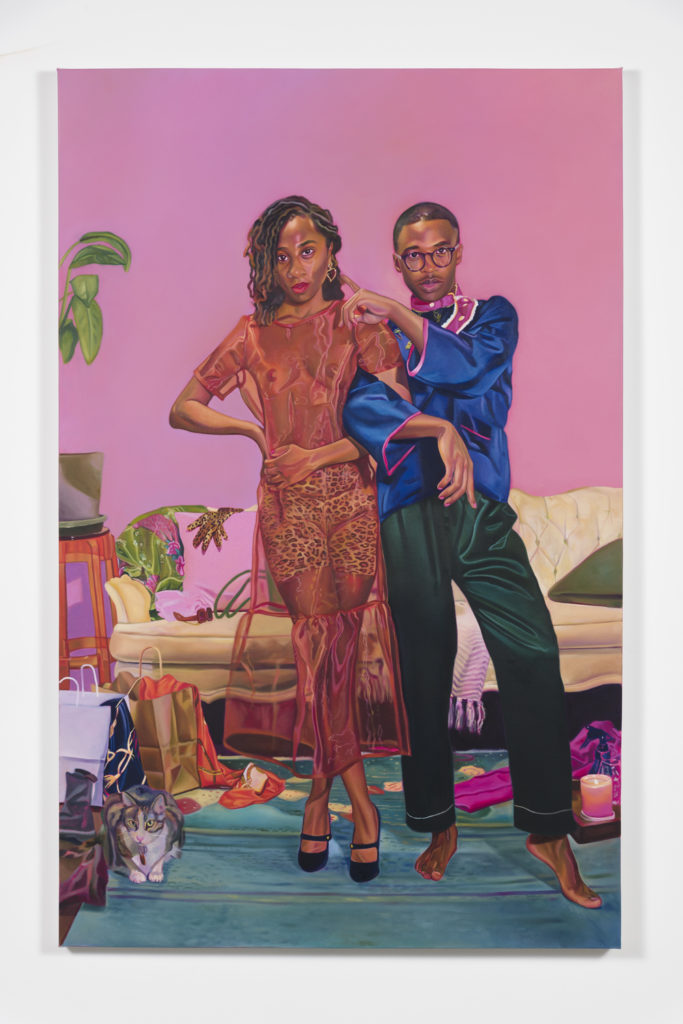

Jarvis Boyland, Mood for Love, 2018. (Photo by Jeff McLane. Courtesy UTA Artist Space)

Six painters contribute significant large-scale works to a dynamic group show comprising a range of aesthetics, styles and narrative strategies, all centered around representations of the male figure, especially men of color. In Disembodiment, curator Mariane Ibrahim is committed to an updated canon which recognizes that a universe of stories and styles exists, created by black artists, depicting people, that are nevertheless not engaged — or, not only — in a dialog on identity. Instead, or additionally, these artists are advancing a broad, diverse and robust conversation with the very notion of portraiture across art history and fine art technique.

Although there is a good deal of critical theory scrutinizing the fetishization and othering of black bodies in Western art, and also an active interest in works that unpack varieties of black experience, one thing that’s lacking is parity in the canon, and the institutions. In the portrait and genre, artists frequently take inspiration from moments in their own everyday lives —be they solemn or celebratory, public or private, sexualized or serene, folksy or fantastical. This part of art history has, unsurprisingly, been dominated by the lived experiences of white men. White male ideas — and white male bodies — are posited as the norm, anything else is othered, strange, the exception and that is that.

The quiet subversion of a show like Disembodiment is to privilege the black artist’s everyday body as a countercurrent to the status quo, and to examine the eclectic mannerisms of its authorship and expression on equal footing. Quiet not because the work itself is subdued; it is anything but. Rather, the show’s tactic is a quiet one: All the work possesses such presence, personality, advanced skill and distinctive voice that the fact of the painters all being black men — while remaining central — becomes, by curatorial design, incidental. It’s just some flat-out incredible contemporary studio painting, and it belongs in the art history books on the merits, and that right there is Ibrahim’s whole point.

Jerrell Gibbs, Breakthrough, 2019, Oil on canvas. (Photo Jeff McClane. Courtesy UTA Artist Space)

Works like Jerrell Gibbs’ have a cloistered awkwardness, a balance of stillness and wildness, that speaks to existential stretches of waiting and remembering. His way of moving freely between crisp rendering and schematic abstraction, and his penchant for earthy palettes, metonymic impasto and roughed-in settings has a certain literary quality, like scenes from a novel.

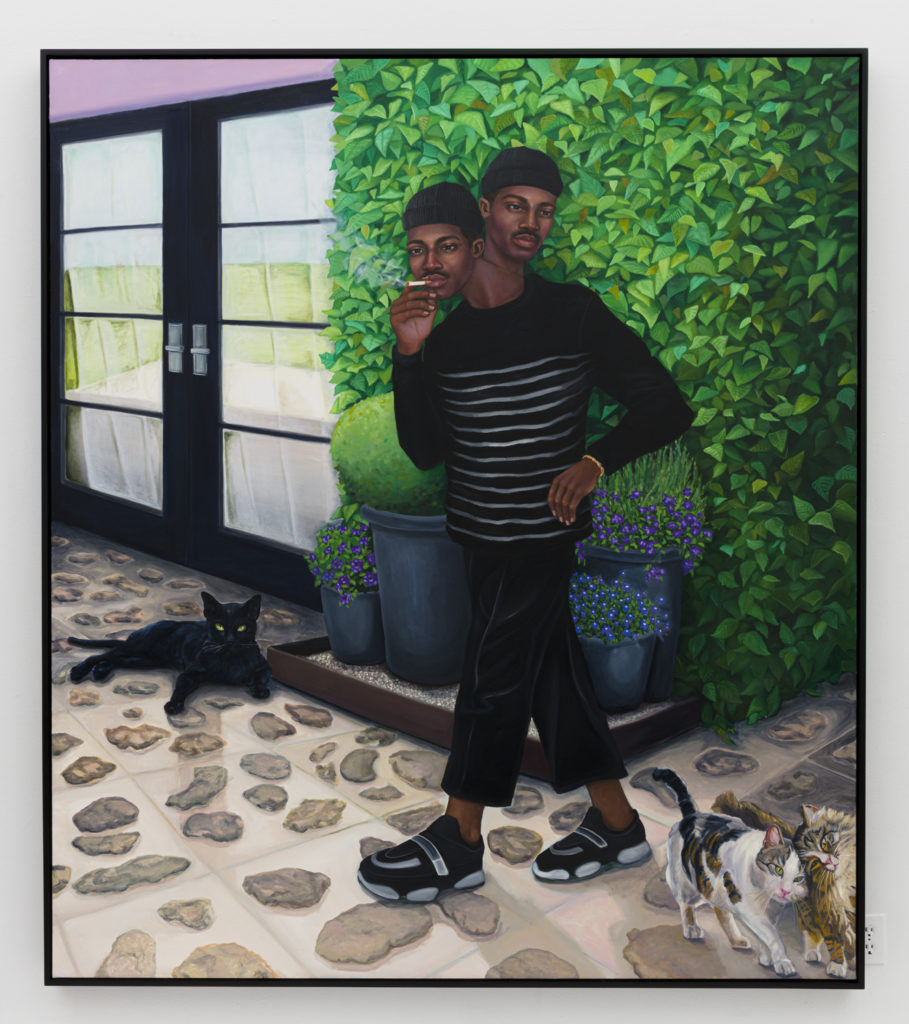

Vaughn Spann, Black Catz, 2019, Oil paint on canvas stretched on aluminum braces. (Photo by Jeff McLane, Courtesy of UTA Artist Space)

Also interested in the forced intimacy of architecture and nature, as well as ways of depicting the multifaceted nature of human consciousness, Vaughn Spann brings humor and a chic, stylized wit to the scenario of a man on a walk, having a smoke to clear his head. At the same time, Spann’s patient, almost devotional attention to endlessly detailed pattern and a slightly hyperrealist saturation and tight focus have a classically retro swagger inside a totally contemporary sensibility.

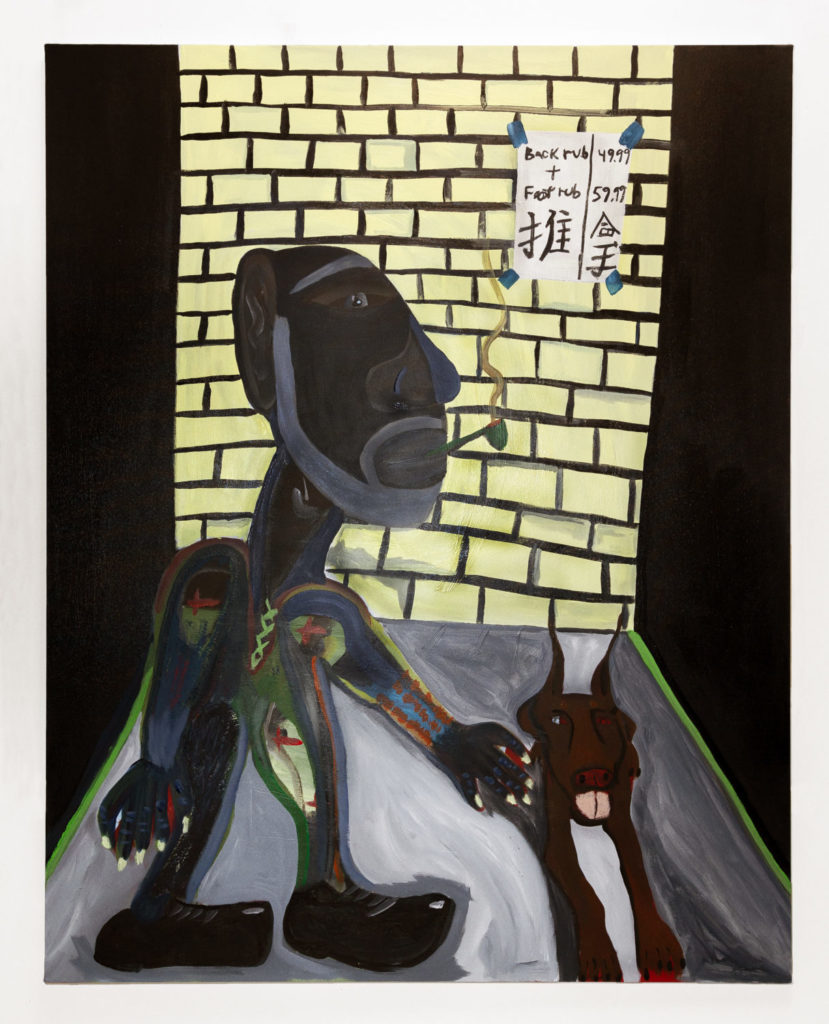

Marcus Jahmal, Chinatown, 2019, oil and pastel on canvas. (Courtesy of Various Small Fires)

Marcus Jahmal’s urban folk has a jaunty soulfulness, expressed in a looser, more pared-down style than Spann’s, though he too is interested in the spatial incursions of architecture into the public space and the potential for abstraction to find a role within a scene — and in having a smoke while thinking things over.

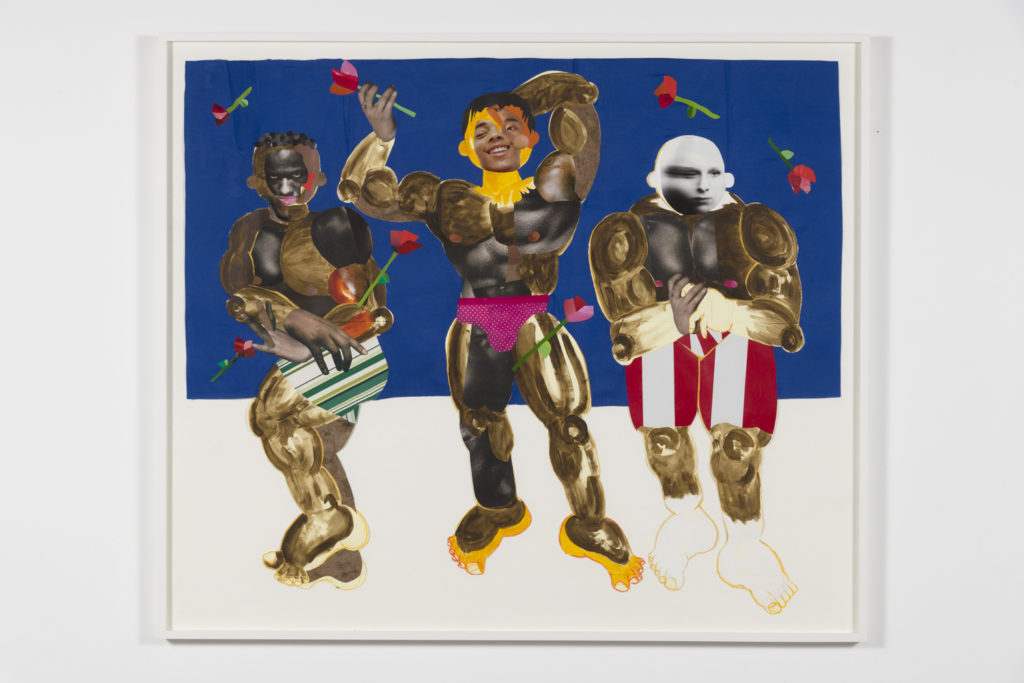

Clotilde Jimenez, The Contest, Mixed media and collage on paper. (Photo by Jeff McClane. Courtesy UTA Artist Space)

Clotilde Jiménez uses collage as both a metaphor and an actual technique for building a composite, fluid identity and performing masculinity, in large scale works with inflections of cubism, Leger-style futurism, and even Willem de Kooning. Jonathan Lyndon Chase is also adept at infusing his paintings with the energy of performance, and in engineering a hybrid style of vibrant colors and striking lines. His interrogations of queerness in the odalisque modality are so lush as to be almost experiential. In this show, he tries something new — the extension of pictorial space into the real space of the gallery, by way of an installation of piled red shoes tumbling to the floor.

Jonathan Lydon Chase (Photo by Jeff McClane. Courtesy UTA Artist Space)

Finally, Jarvis Boyland is everything. His contributions are showstopping in their flirty, perfectly formed, bohemian and self-conscious beauty. A love of rich textiles, shiny and translucent, animal prints, impossible expanses of aggressive deep pink, the elegant disarray of luxury, and a gender-fluid confidence all combines into disarmingly powerful portraits and interiors that give shades of Prince and Mickalene Thomas along with quirks of style that somehow channel the jazziness of the 1930s, the Pattern & Decoration moment of the 1980s and the Paul Smith selfie-wall present-day, all at the same time — while celebrating friendship and the timeless, poetic melodrama of a youthful inner life.

Disembodiment is on view through January 25 at UTA Artist Space, 403 Foothill Road, Beverly Hills; utaartistspace.com.

Jarvis Boyland, Pop Out, 2019, Oil on canvas. (Photo by Jeff McLane. Courtesy UTA Artist Space)