Rock ‘n’ roll is always a multi-sensory experience. But as far as scenes go, downtown New York City in the late nineties and early aughts — where the genre was reforged by bands like The Strokes, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Interpol and LCD Soundsystem — was a particularly colorful, pungent, tactile and delicious one.

In 2017, journalist Lizzy Goodman immortalized the odors and colors of the diseased bars, awful apartments and drug-fueled dance parties where that scene was born, in her singular oral history, Meet Me In The Bathroom: Rebirth and Rock and Roll in New York City 2001-2011, as well as the now-legendary concerts, studio sessions and star-studded backstage gatherings that came later. She introduced the younger half of the millennial generation (who were learning to read while The Strokes were doing their first lines) to this world. Meanwhile the elder half and the baby boomers who might’ve been there were given the chance to reflect on that time, now illuminated by everything that came after.

Without writing a word of standard music critic post-hoc theorizing, the text is entirely Goodman’s curation of 200+ interviews with artists, managers, label execs, producers, music writers, barkeeps, doormen and more. Through the voices of the people who lived it (she did too, for the record), Goodman makes sense of the why and the how of this scene, in all its disturbing serendipity. It was gestated in between the moment rock lovers had given up and submitted to Coldplay, the 9/11 attacks, the rise of Napster, Twitter and Pitchfork, and the fall of the record industry as it was known until that point.

“There was a generation born in a moment where you’re nostalgic for the present. It was like, ‘Oh my god, everything is so fragile.’ To feel that when you’re 22 and doing drugs and partying and going out all the time and wanting to make art, it creates this extra sense of mania and urgency, on top of the mania and urgency New York artists already feel,” Goodman summarizes.

Two years later, Goodman has turned Meet Me Into the Bathroom into the vibrant, gritty, sensory experience her book demands. The book’s visual counterpart: “Meet Me In the Bathroom: The Art Show!” co-curated by Goodman and Hala Matar, presented by Vans and organized by UTA Artist Space, opened last week at the downtown gallery The Hole (owned by gallerist Kathy Grayson who recently lent PAPER her dog Bertie the Pom for a fashion editorial).

The exhibit is curated differently than most music exhibits. It has the usual mix of ephemera (tour posters, instruments, album artwork, Karen O’s chewed up microphones), visual offerings from musicians from the scene (paintings and sketches by Karen O, Interpol’s Paul Banks, The Rapture’s Luke Jenner, The Moldy Peaches’ Adam Green) and vignettes by photographers who were hanging around like Ryan McGinley and Colin Lane (plus, less expected documentarians like Roman Coppola and Spike Jonze). However, it also includes large-scale, conceptual pieces from galleried artists like Dan Colen, Doug Aitken, Rob Pruitt, Rita Ackermann and Adam McEwan — whose links to the scene are abstract and provocative.

“Sometimes the connections were literal, like Ryan McGinley who photographed The Strokes a lot. But it’s also work that was ideologically integrated with, or a mirror for the ethos of the music,” Goodman explains. “It’s either people who knew the Yeah Yeah Yeahs and The Strokes and Interpol, or, who would’ve been drunk in the same bars, hungover on the same mornings, reading the same New York Post, Page Six stuff over the same bodega coffee, during that extra long February we lived through, like they would’ve been in the same summer blackouts. People who had that shared sense of oxygen.”

What were the molecules in that oxygen? “The work had to feel unsafe in a certain way,” Goodman says. “The thesis was that each work has to conjure this sense of unrest, danger, instability, excitement, of getting away with something. The same stuff the music in that era and then the stories in Meet Me in the Bathroom are exploring. The show is really about a feeling: Our goal is that you’ll walk into this space and feel a little bit ill.”

The exhibit starts in 1994 with Rita Ackermann’s painting “We Mastered the Life of Doing Nothing” (which Goodman says transports her to the bored mischief of the Kids-era New York of Chloë Sevigny and Harmony Korine), and goes up to a 2019 sculpture by Rob Pruitt that’s so perfect for “Meet Me in the Bathroom” you’d think it was commissioned: two pairs of stuffed jeans positioned on and next to a toilet, as if they’d ducked into the bar bathroom for a quickie. The curation is distinctly non-linear, which deliberately represents, according to Goodman, how “New York is this ever-evolving organism, there’s a very quickly shifting legacy of who you’re being influenced by, or playing with, it’s this weird sliding doors between one era, and the next.”

Meet Me in the Bathroom was a wild success. Aside from the art show, the 600-page book is also being adapted into a documentary miniseries. Goodman has a theory on why: “This era has a lot of allure and intrigue right now. There’s a sense of mourning, which is why the show feels contemporary to me. We’re in a really challenging, bleak time. We’re asking questions we thought we had answers to, like ‘What is America? What is Western society?’ I think the nostalgia for that time we’re experiencing is about trying to understand how we got to now. The genesis of now, is that chunk of time: the first decade of the 21st century.”

PAPER had Goodman walk us through 11 of her favorite pieces in the show— to help us understand why she chose them, what they say us about NYC in the ’00s, and what they have to teach us about 2019.

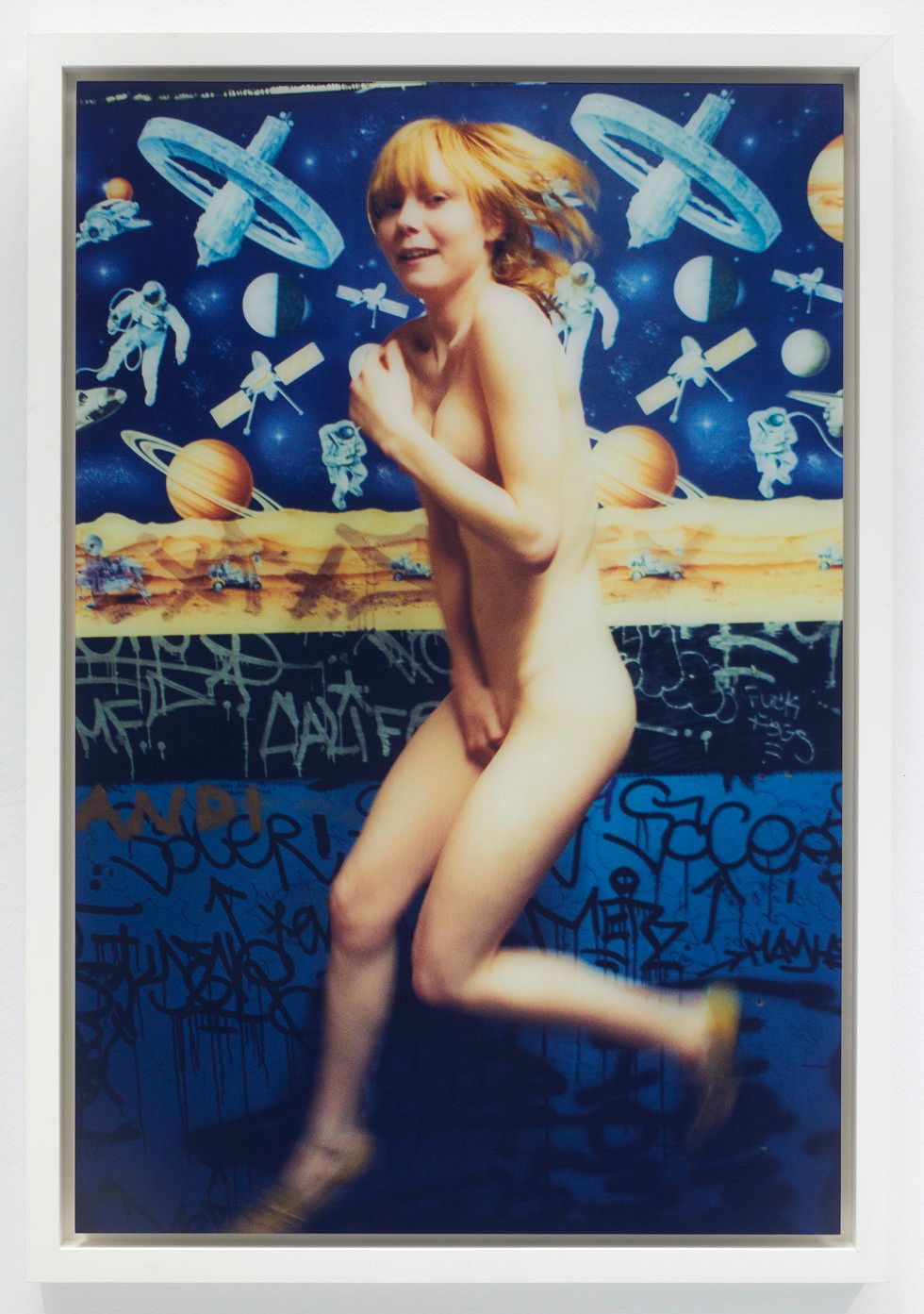

Ryan McGinley, “Lizzy” (2002)

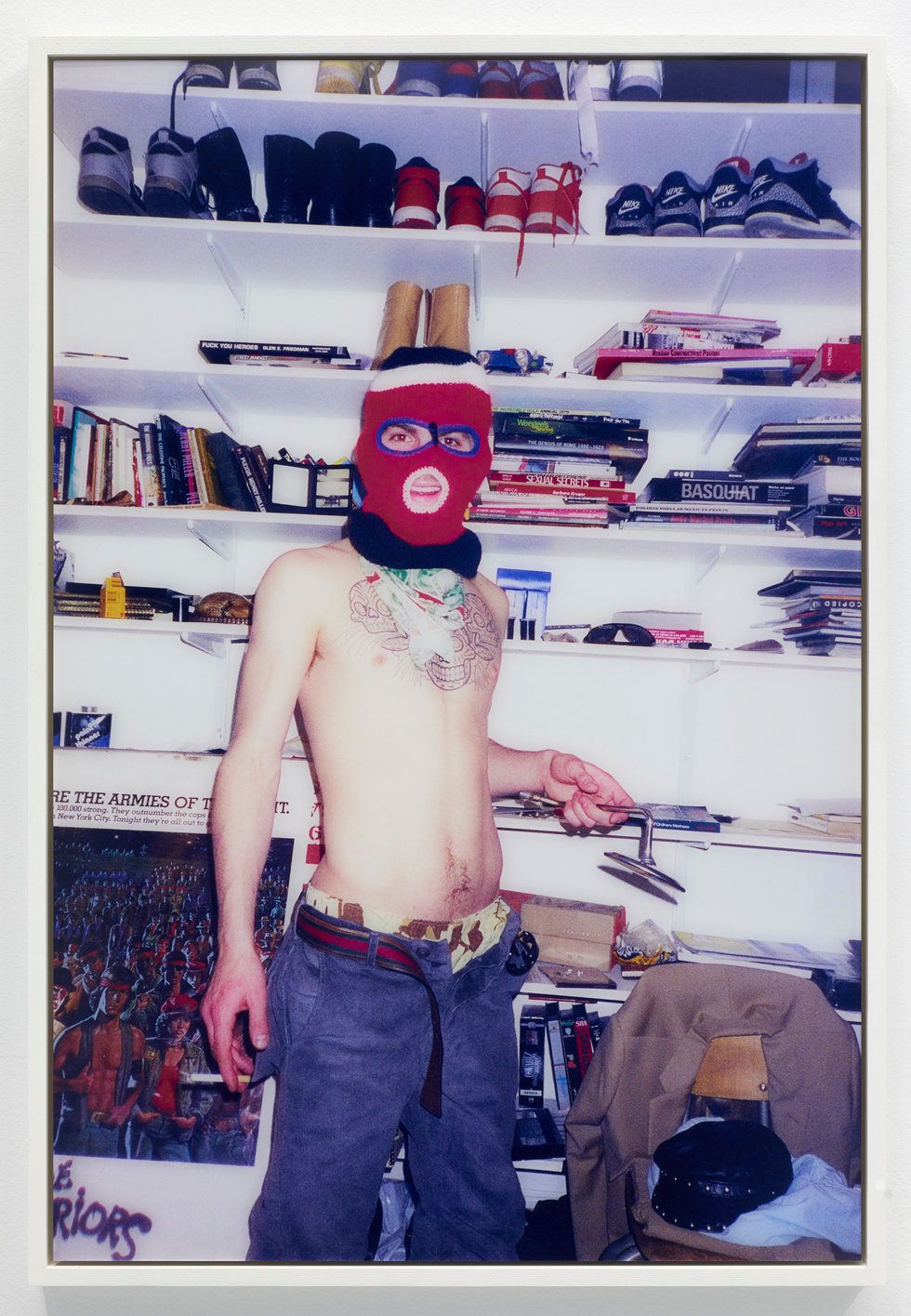

Ryan McGinley, “Ski Mask” (2001-2002)

Who is better at capturing the beautiful danger of youth in action, than Ryan? You look at these images and I just feel this tug at my previous self, and a kind of concern for her (“Lizzy”) and just this sense of total freedom and elation and beauty. That’s the money shot for this show. That’s like exactly what we’re aiming at.

“Who is better at capturing the beautiful danger of youth in action? [Than Ryan McGinley]. You look at these images and I just feel this tug at my previous self.”

Ryan is who you would think of first in some ways — a major visual artist who has obvious creative and literal connections to this world. Everyone knew how Ryan McGinley was. I didn’t know Ryan at the time, but oh my god, we must’ve been in so many of the same bars. I just knew him as a dude who was around the bars and friends with The Strokes. I mean that’s kind of the whole point. There was this weird democratized period of time where you’re just out and people are making stuff, and you don’t know where it’s going to go, or whose going to get famous.

Urs Fischer, album cover for ‘It’s Blitz!’ by Yeah Yeah Yeahs (2009)

At first, as a rock kid, it’s just like: “wow, like what a cover.” Then you’re like, who made this? It’s one image like that, that every Yeah Yeah Yeahs fan would see and would feel. I mean, God is that them? The chipped nail polish, the delicacy of the hand, the violence of this sort of mid-air — the whole inherent ephemeral nature of the image. It’s all disappearing, right? It’s an action shot. There’s this sense of the gleeful grossness of it. It’s just like, “ooh, the yolk on her.” It hits me it’s the same place where seeing Karen spit beer at a Yeah Yeah Yeahs show hits, in a joyful fountain, on stage, with her head tilted back.

“There’s this sense of the gleeful grossness of it… it hits me it’s the same place where seeing Karen spit beer at a Yeah Yeah Yeahs show hits.”

I don’t know how Urs ended up taking this. But I mean, at any moment in New York, there’s a hundred scenes happening. This is what I love about the city. It’s like, if you looked at Barakat — I don’t know if you know it, it was this amazing Middle Eastern place open till after last call on the Lower East Side. If you did a DNA analysis of every human ordering a falafel in Barakat on any given night in 2005, a hundred different worlds and nights would open up to you. Like there would’ve been a rock kid night, there would’ve been an art kid night, there would’ve been like a dance scene person, there would have been like a bunch of burlesque performers from The Slipper Room from down the street, eating their falafel. There would be a bunch of square dudes from Wall Street who’d been up too late! There’s this collision of all these different realms. I think that’s how Urs shot It’s Blitz! and that cover happened.

At these early conversations with Hala and Kathy [Grayson, owner of The Hole], it was like “Hey, we asked Urs and the band if they would be cool if he displayed the photo.” Then it was like, “Let’s get some other work from him if we possibly can.” Hala and Kathy were nerding out and being like, “Oh my God, what if we could get this or what if we could get that?” Then I googled and was like, “What about, you know, the tongue?”

“It’s so foul and upsetting… but I also want to get as close to it as possible and that’s it. That’s the energy.”

I’ve learnt so much making this show, because my knowledge of the scene has been experiential rather than intellectual. I have not studied this work before. But it makes total sense that this is the same artist behind that piece. It’s like, “What else is there to say about that work?” It’s so foul and upsetting… but I also want to get as close to it as possible and that’s it. That’s the energy.

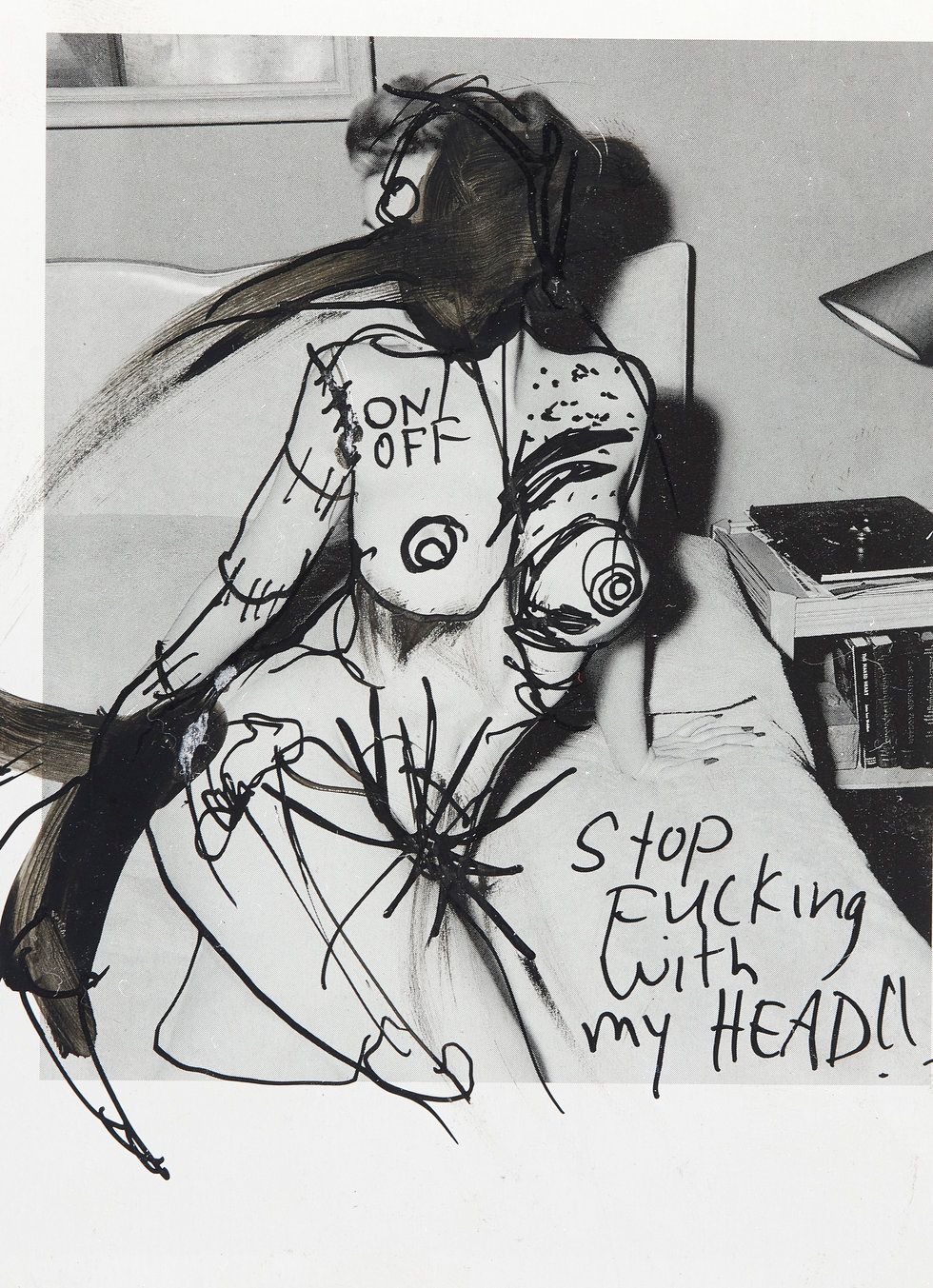

Karen O, “Stop Fucking With My Head” (2001)

There’s such a joyful rage to this one, which is what the Yeah Yeah Yeahs and Karen are all about. That blend of darkness with light. This piece is coming from such a dark place, but it’s so bright. I think there’s a lot of romance to the things Karen draws. Her sketching is doodle-y, in a serious visual artist way. It’s as if you’re getting to be in her head, while she’s in a class she doesn’t want to be in. It’s electric and immediate and emotional, which is really her. She has these drawings that came out with her solo Crush Songs EP, which aren’t in our show but are available if you get the vinyl. They are just these beautiful erotic sketches of girls and boys making out. They’re just so sweet, and sad, and emotional.

“It’s as if you’re getting to be in [Karen O’s] head, while she’s in a class she doesn’t want to be in.”

Her Crush Songs drawings, which show a different side of her, which is more the side that presents in person. She is such a girl and it’s very “I wanted to move to New York so I could meet cool rock guys.” [laughs]. Which is like, “Oh my god, you’re allowed to say that!” What we have in the show are more the Karen O that’s a fucking serious force of nature — that’s reflected in this sketch.

Christian Joy, costumes for Karen O (2003-2013)

Christian Joy is a straight up genius. I truly think she is one of the most interesting artists of any medium, in this era. Part of why I’m so obsessed with her relationship with Karen creatively, is because it comes with so much aggression and violence. As you’ll read in the book, Karen and Christian would go out and just start trouble. We’re talking about a scene where there’s almost no women (to our collector’s dismay) and great loss. Here are these two fuckin’ shit-stirring, trouble-making hellions — little pixie cut hellions. They would just go out, have some tequila, they would pull each other’s pants down, they’d physically fight. They’d like, mud-wrestle almost, and show all this aggression with big smiles on their face. It’s like they have their own fight club. They had this incredibly combative party relationship that was also a performance.

“We’re talking about a scene where there’s almost no women… Here are these two fuckin’ shit-stirring, trouble-making hellions.”

You’d have to ask them about what that says about femininity, but as a fan of Karen and Christian’s in those early years, it was really influential on my own sense of what was allowed for me. It was like — “I can do whatever the fuck I want.” They were the most punk thing on the scene to me. There’s this one dress called the “What’s eating Karen O” dress, which is like acid green. She talks about it in the book how she felt physically sick putting it on because it was so ugly, even though she wanted to wear it.

“The idea of pursuing hideousnesses as a form of beauty is so key to these years.”

The idea of pursuing hideousnesses as a form of beauty is so key to these years. There’s this sense of question — “When did we decide that looking good is looking cool?” I’m all for beauty but every tool we all use now like filters, airbrushing — it digitally smoothes over the lives we are leading. In its extreme, this too is interesting and arty when you take it to the max. When it’s neutrally applied, we are just sanding off everything that makes life interesting. That’s what I love about this dress. It’s celebrating dirtiness and ugliness and harnessing that into beauty.

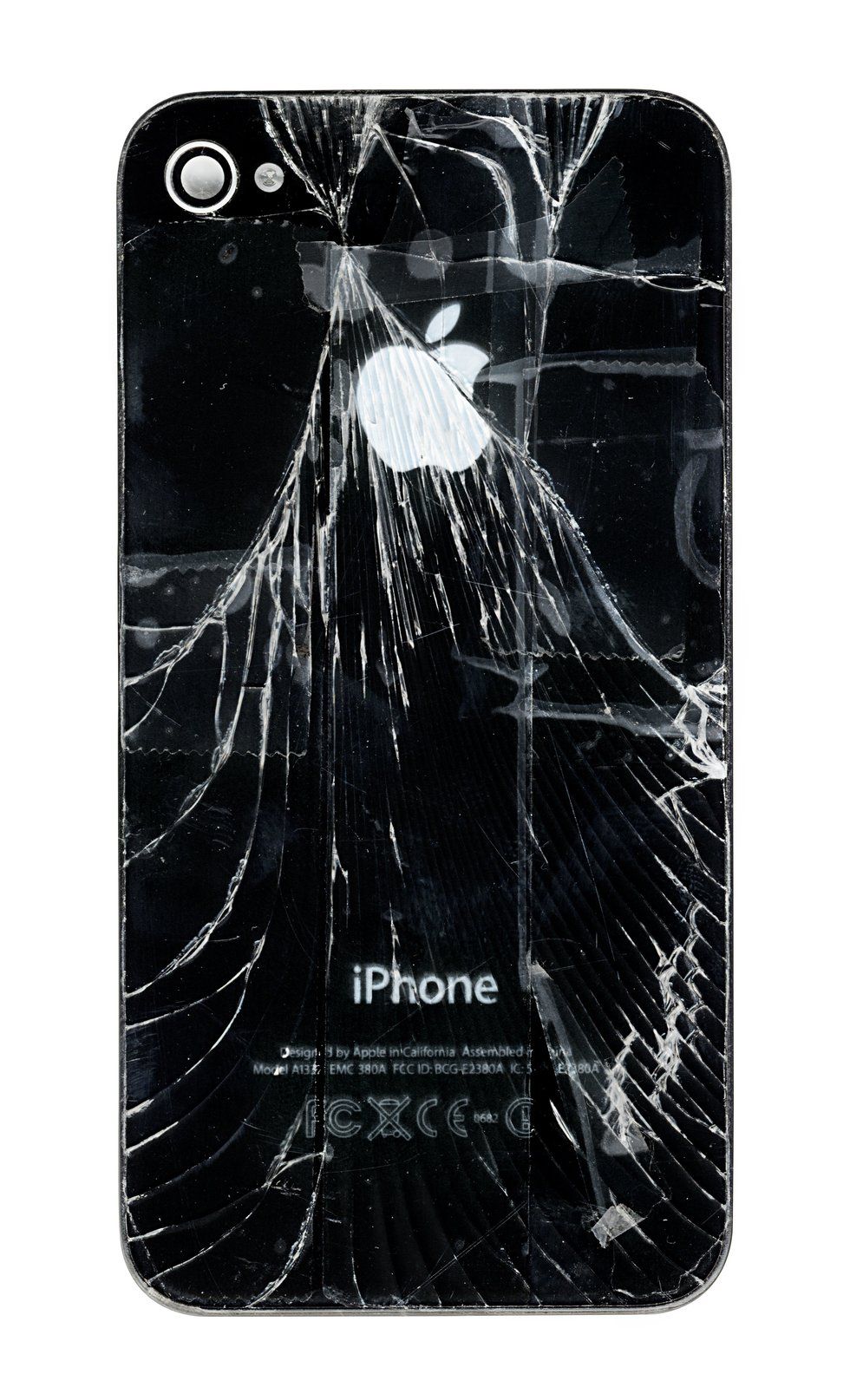

I’ve talked a lot about the importance of ugliness, as a value that exists in punk, as an art aesthetic. Not just in music, but like the idea of punk as opposed to punk rock. Ugliness is disruptive, just like beauty can be disruptive. One of the things we had going for us in this era — even though it was post-Internet, we had email, lots of us had cell phones — but the idea as a personal computer as a surrogate hand wasn’t there.

“You had space to be ugly. You did not think someone was going to photograph everything that you did.”

You had space to be ugly. You did not think someone was going to photograph everything that you did. Every outfit was… you could fuck around more because there was a sense of play. Dirtiness was valued, but even if you drop the idea that it was valued, it was just like, “You can go get ugly and see how that goes and not worry that that photo is going to haunt you for the rest of your life.” That’s what I think about when I think about that piece. My emotional response to it is, “How many times have I wanted to do that? Have I wanted to revolt against my own technological addiction? Have I wanted to just take that thing and like take a sledgehammer to it?” It’s so satisfying. It’s just this sense of violence and revolt against the situation we’ve all put ourselves in.

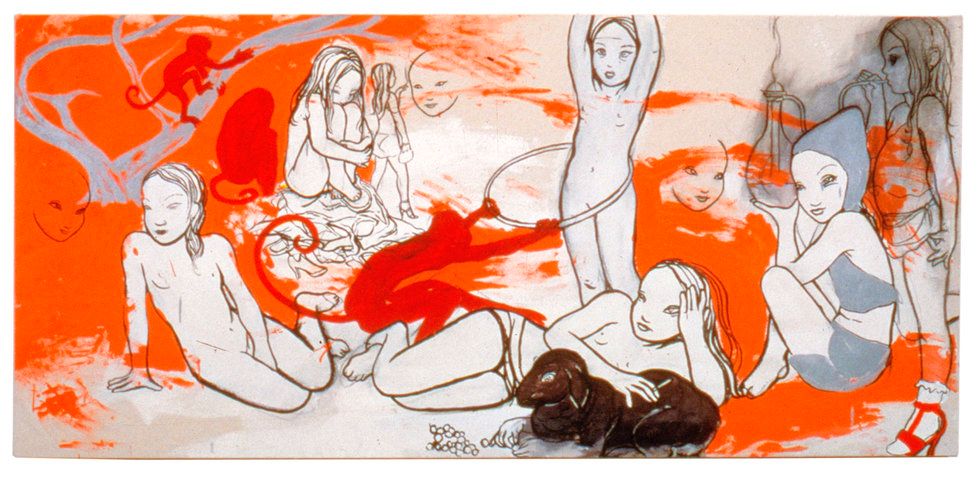

Rita Ackermann, “We Mastered the Life of Doing Nothing” (1994)

With this, I was thinking about how New York stories are a series of layers. It reminds me of this Kids era of New York, like Harmony Korine and Chloë Sevigny. There are these layers, of the story of people five years younger than you, five years older than you, two years older than you, who just moved here last week you’re being woven, and they’re being woven into your story. A lot of Rita’s work feels so much like that version of adolescence — the one kids were inspired by when I moved to New York in 2002. That Kids era was the most recent story of what adolescence looked like: you move to the city, come to the most beautiful and exciting place in the world. And then you don’t do anything at all. You just lounge around with your friends and wander the streets aimlessly seeing what sparks interest.

“That Kids era was the most recent story of what adolescence looked like: you move to the city, come to the most beautiful and exciting place in the world. And then you don’t do anything at all.”

Where the book starts, technology had already started to change that capacity for nothingness. We are documenting it now, so many people are feeling nostalgic for it, including myself. This painting conjures how I felt when I was 22, being like, “Man, they were so cool.” Of course, that era was about three years before I got to New York, but that’s how time works. When I was in high school it was just like, “Oh my God, they were just here like being the coolest New York kids ever wandering around the East Village using pay phones. How glamorous, like looking for apartments in the Village Voice.” I remember hearing this story from an old boyfriend and thinking, “Oh my God, he’s so cool.” He was like, “Yeah, we all used to get in line outside when they would deliver The Village Voice on Thursdays. Pretty sure it’s Thursdays. And that’s how you found your next apartment or your next bandmate. It was like, “Oh my God, that’s so romantic. You know?” That’s what I think about when I look at this photo. It’s like my own, the sort of legacy of the idea of New York, that this book was built on, captured in one image.

“We get to look at this all in retrospect, with a new perspective on what you loved when you were 24. You’re going to have different thoughts on your present, as well as the past that you’re romanticizing in the present.

Also — in many ways, this image is disturbing. It’s not okay. There’s a real danger of romanticizing the things you’re drawn to. That’s an important element of the show. We get to look at this all in retrospect, with a new perspective on what you loved when you were 24. You’re going to have different thoughts on your present, as well as the past that you’re romanticizing from the present, and what you imagined your future would be like. Both the book and the show should be like looking through a kaleidoscope. It’s prismatic. A sort of visual choose-your-own-adventure. You look at it one way one day. You look at it the next day and it’s gonna have a completely different tone. That’s part of it too, like, why was I idealizing this? Everyone is really messed up, it turns out. A lot of the things that felt sweet to me are not, when you look back as an adult in the same way. It’s important in the show because it’s beautiful and upsetting. It’s also sort of part of this aesthetic tryptic, that tells you where you have been and how all of these works sit in concert with each other.

Rob Pruitt, “Studio Loveseat (Xtra Long)” (2015)

I’m obsessed with this one. So, it was made in 2015, which is a bit out of the parameters we loosely tried to use. We were aiming for earlier, but we asked the artists, “What comments on that time for you?”

It’s whimsical. As a piece of art, it conjures this sense of lightness, in darkness, that I think Karen O gets at really well in her artworks and her performances. Christian Joy also touches that. That is so key. That’s part of what distinguished the early ’00s scene from the nineties scene — the sort of alt rock, grunge, like Kate Moss, Kids scene that we’re talking about before. There was this real pursuit of joy, born out of 9/11 and the dawn of technology and the world ending. There was this sense of like, well fuck it, let’s pour glitter over everything, because we’re going to die. It wasn’t sunny by any stretch, but it’s willfully joyful and willfully colorful. The 90s were full of heroin and black turtlenecks. And then Karen O poured glitter all over herself and started eating her microphone and it’s like, “This seems much better” [laughs].I think that couch feels whimsical in the way that I was searching for. That was an important part because we inherited a New York that felt very grim.

“There was this real pursuit of joy, born out of 9/11 and the dawn of technology and the world ending. There was this sense of like, well fuck it, let’s pour glitter over everything, because we’re going to die.”

That’s one part of why we picked this piece. The other is that the space itself, the whole gallery is named after this bar, The Hole, where we always used to go to, which was absolutely disgusting. There were these disgusting couches, I call them hepatitis couches. They were like the furniture that you crossed the street to not have to walk near in New York, ’cause it’s like, “I’m going to catch bed bugs.” Rob Pruitt’s couches are beautiful pieces of art obviously, and not foul in any way. But it fits, because even though we’re sort of idea of recreating the whole bar in the gallery, it’s an impressionistic recreation. Some of it is literal but some of it isn’t.

Dash Snow, “Untitled Polaroid” (2004)

Dash was one of the first artists we knew had to be in this show. Nate Lowman, Dan Colen, Dash Snow, and Ryan McGinley were almost in a band of their own. I’m making that up, but they were influencing and hanging out in each others’ creative lives. I knew who Dash Snow was at the time — everyone did. This artist, who was running in our midst, built a world around an aesthetic, coming from the same primal place all the bands are coming from.

“I keep returning to it — this sense of insurgency.”

There was this sort of awareness and fragility to what he was doing. His work is all the things we are talking about. I keep returning to it — this sense of insurgency. There is a sense of trying to break down the boundaries and limitations of your immediate world, to make something transcendent and beautiful. That’s cliché of course, because it describes every art movement. What changes is the bounds and limitations in that particular era. Dash’s work to me, especially this particular polaroid, is a really micro portal into that world [laughs]. You look at that and you’re like, “Oh. This is that world in a nutshell.” It looks lived in, in a way that brings me out. Not back in, because it’s not retrospective. It shows me exactly what that energy looks like. So you see it, and it’s like, “Ok. There it is. If you’re ever wondering.”

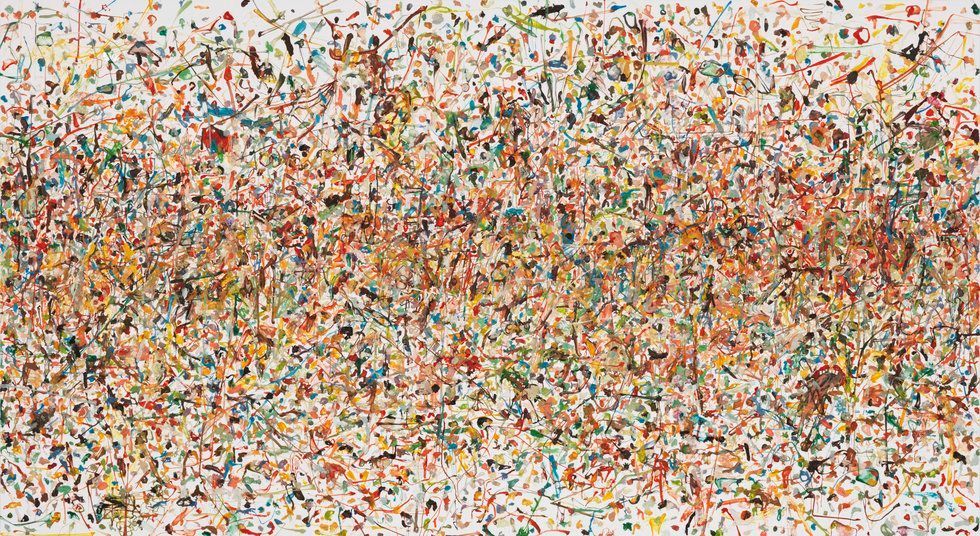

Dan Colen, “This Isn’t So Dark” (2010)

Dan Colen is so amazing. I read this quote from him recently — I’m paraphrasing, but — he says something along the lines of, “People always thought I was fucking with them, but I was really just trying to say something true.” When an artist says, “I’m gonna paint with gum,” it’s taken as irony and read cynically, a parody. People see it and go, “Oh what, you paint with gum? Art is meaningless.” Like those famous stories of people in galleries looking at a toilet and being like “Oh, that’s so moving, it means so many complicated things!” But like no, that’s an actual toilet and someone is going to piss in it.

“When an artist says something like “I’m gonna paint with gum,” it’s taken as irony and read cynically, a parody… His work is a joyful expression.”

I think it’s really interesting to see his work as this sort of joy. That’s like the Karen O stuff. His work is a joyful expression made from actual garbage — gum that has been chewed up, spat out, and discarded. It’s also — gum serves as the backdrop for the griminess of the city. All those little black spots on the city streets are deconstructed gum from all these decades of people spitting theirs out and other people stepping in it [laughs]. That’s what we are talking about here. Like, you’re living in trash — now make something beautiful. I think that, to me, is so important to this era.

Meet Me at the Bathroom: The Art Show is open at The Hole until September 22. You can buy prints of select works here though Absolut Art.

Images courtesy of Cultural Counsel