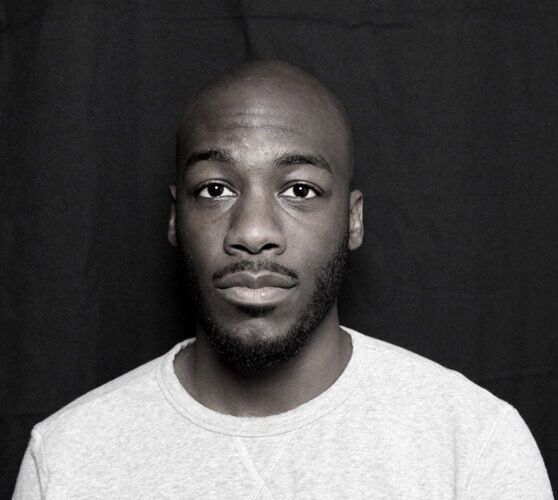

Jerrell Gibbs

B. 1988, Baltimore, Maryland. Lives and works in Baltimore.

Portrait of Jerrell Gibbs by Russell Bunn. Courtesy of the artist and Mariane Ibrahim Gallery.

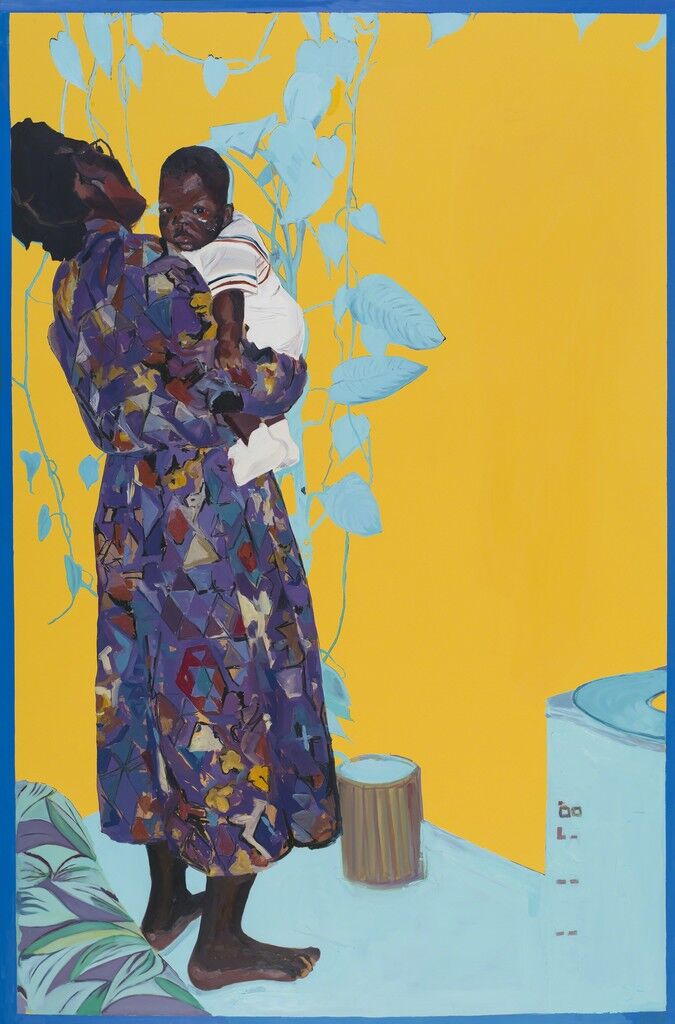

Joy Labinjo

B. 1994, Dagenham, United Kingdom. Lives and works in London.

Portrait of Joy Labinjo by Alexander Coggin. © Joy Labinjo. Courtesy of Tiwani Contemporary.

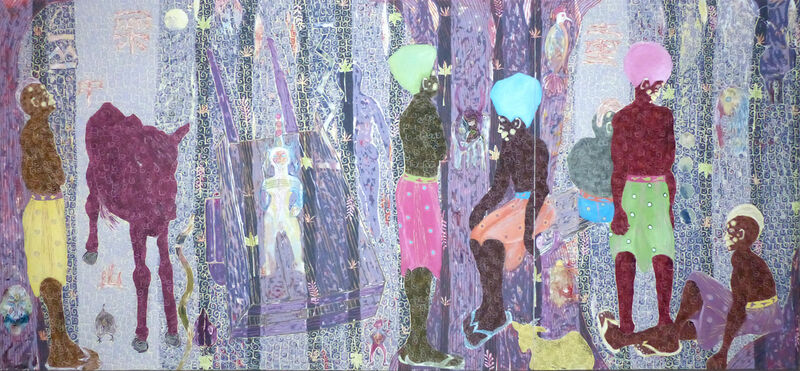

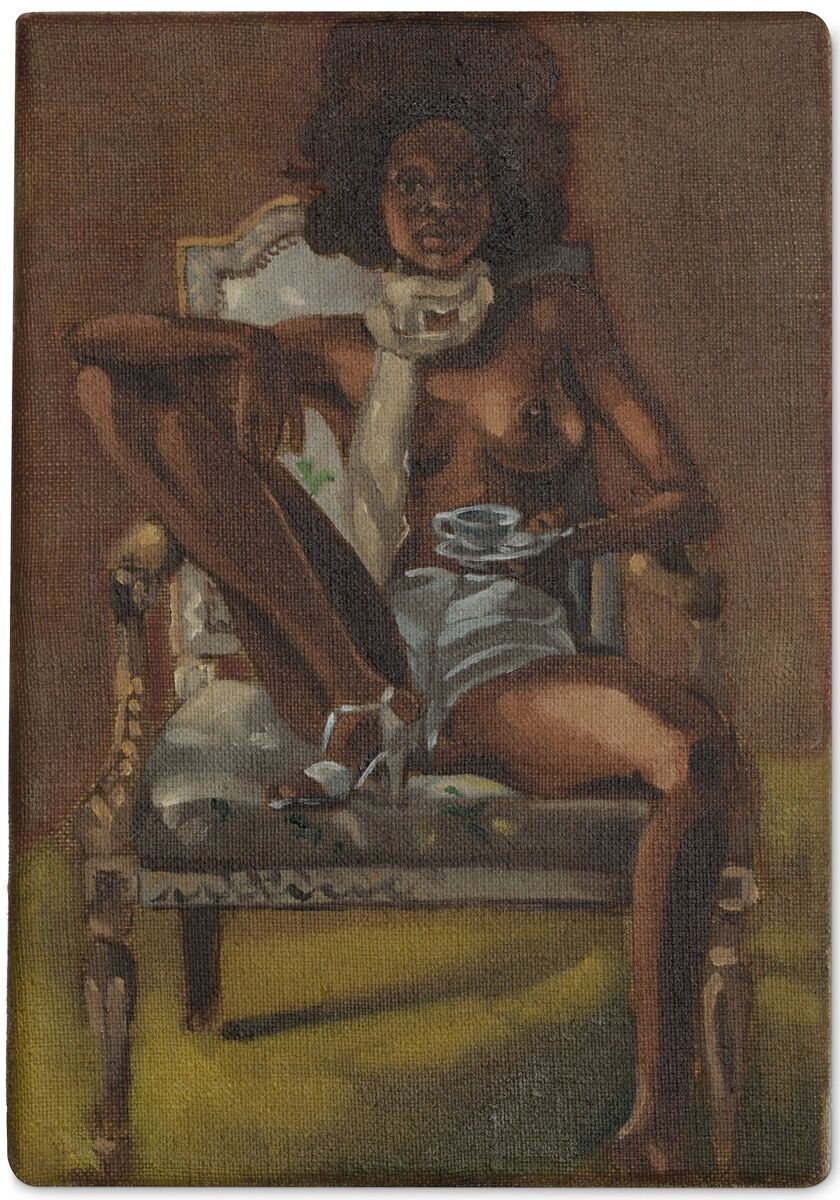

B. 1971, Ziguinchor, Senegal. Lives and works in Keur Massar, Senegal.

Kassou Seydou, Fro-fro, 2018. © Kassou Seydou. Courtesy of Galerie Cécile Fakhoury.

Portrait of Kassou Seydou. Courtesy of Galerie Cécile Fakhoury.

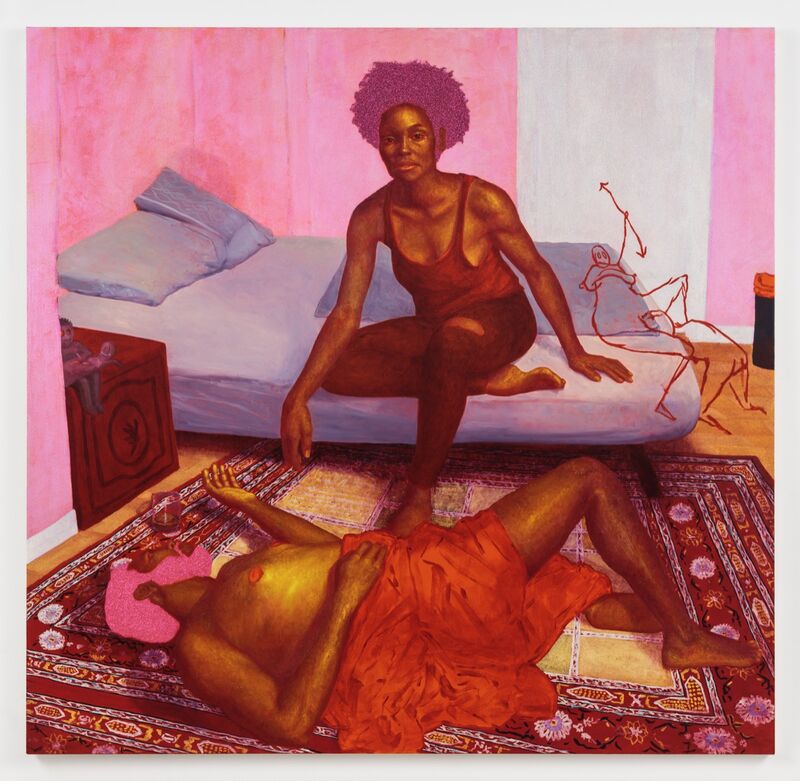

Arcmanoro Niles

B. 1989, Washington, D.C. Lives and works in New York.

Portrait of Arcmanoro Niles. Courtesy of the artist and Rachel Uffner Gallery.

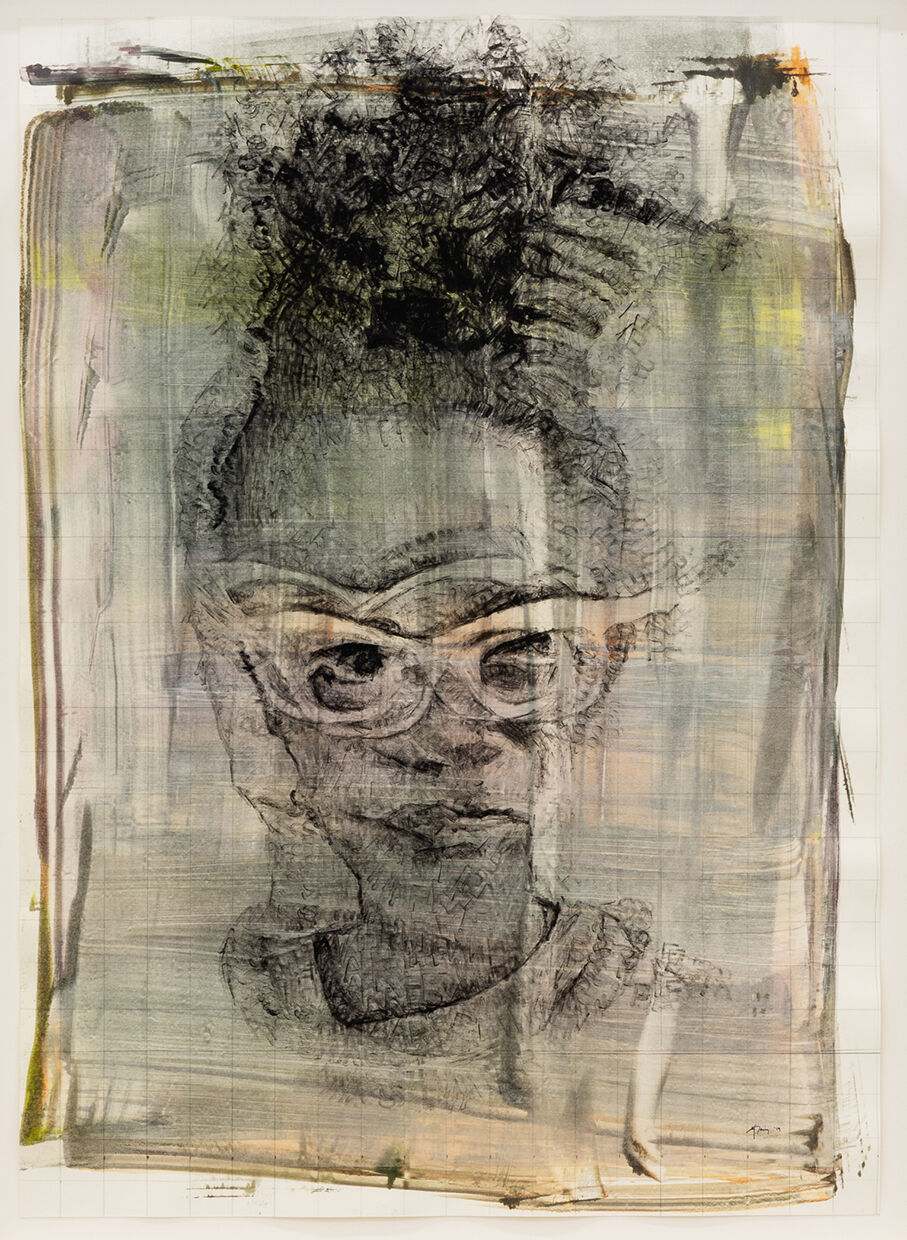

Kenturah Davis

B. 1984, Los Angeles. Lives and works in Los Angeles; New Haven, Connecticut; and Accra, Ghana.

Portrait of Kenturah Davis. Courtesy of the artist.

Kenturah Davis, A Sharp Whisper, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

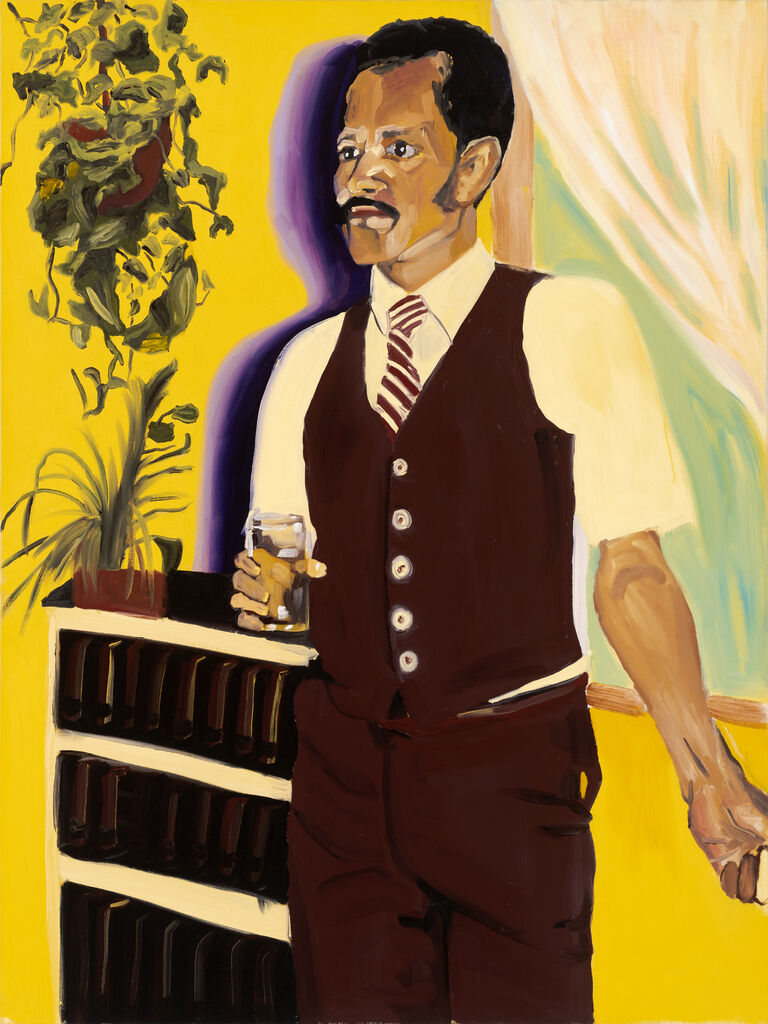

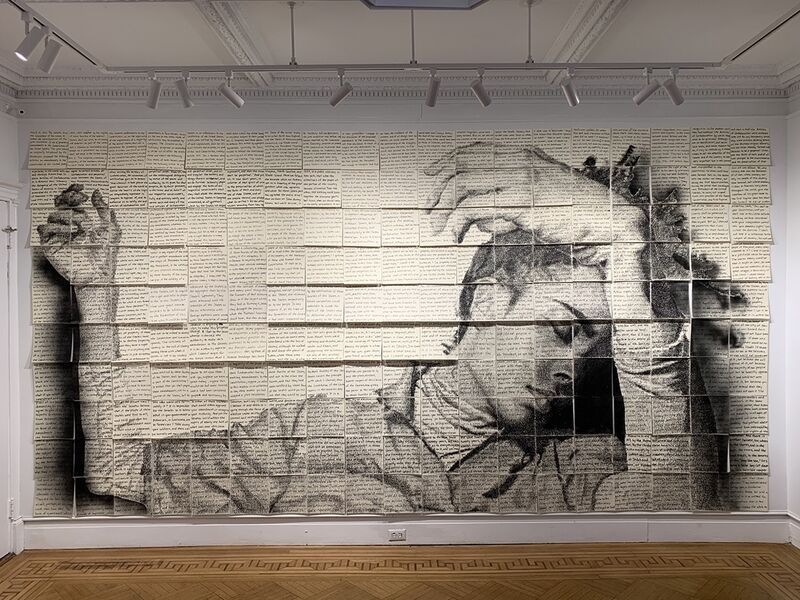

Gerald Lovell

B. 1992, Chicago. Lives and works in Atlanta.

Portrait of Gerald Lovell. Courtesy of the artist and P.P.O.W., New York.

Gerald Lovell, Tia Swint, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and P.P.O.W., New York.

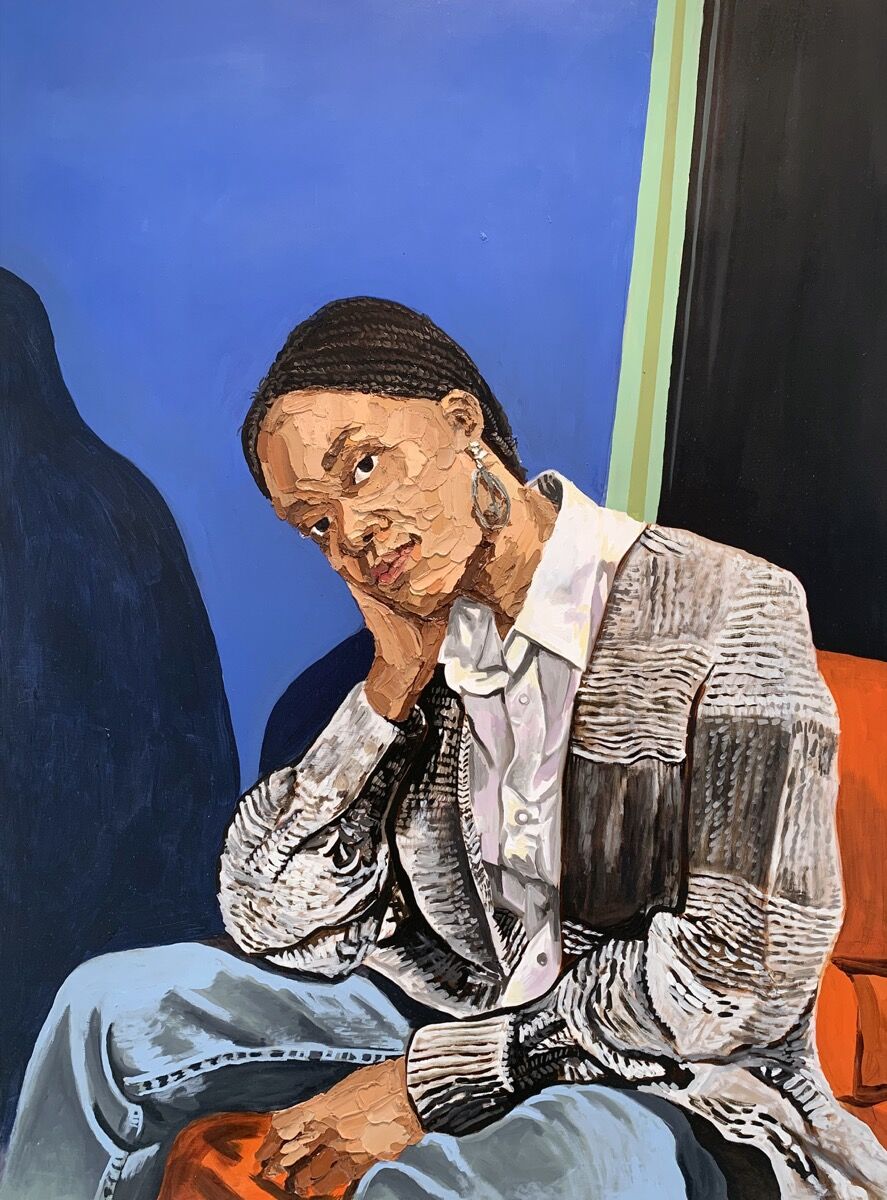

Somaya Critchlow

B. 1993, London. Lives and works in London.

Somaya Critchlow, TBT, 2019. © Somaya Critchlow and Maximilian William. Photo © Kalory Studios.

Somaya Critchlow, Kim’s Blue Hair With Dog, 2019. © Somaya Critchlow and Maximilian William.

Wangari Mathenge

B. 1973, Nairobi, Kenya. Lives and works in Chicago.

Portrait of Wangari Mathenge. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects.

Tajh Rust

B. 1989, New York. Lives and works in New Haven, Connecticut.

Tajh Rust, Rückenfigur II, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

Portrait of Tajh Rust. Courtesy of the artist.

B. 1993, Zimbabwe. Lives and works in London.

Header image: Arcmanoro Niles, “Go Home to Nothing (Hoping for More),” 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Rachel Uffner Gallery.